Source: Buzzards Bay Project, National Estuary Program

(www.buzzardsbay.org/craninfo.htm)

Weweantic River Background Information

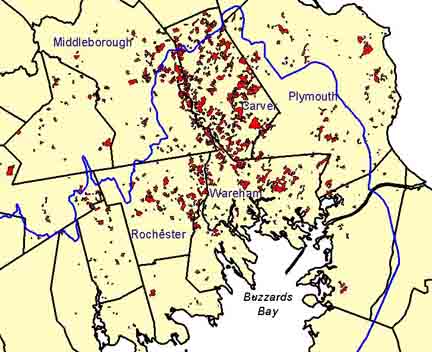

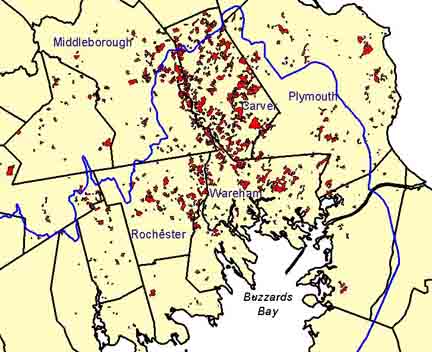

Figure 1: Distribution of Cranberry Bogs in the Buzzards Bay Watershed

Economic Impact of Cranberry Production:

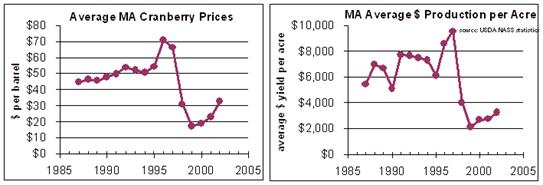

Figure 2. Average Massachusetts Cranberry Prices and Production per Acre

Bogs and Cranberry Cultivation

Background Information

Weweantic River

Massachusetts

Summary information for the Weweantic River site is a compilation of direct excerpts from various websites including Buzzards Bay Project National Estuary Program, the Cranberry Institute, and Cape Cod Cranberry Grower’s Association. Additional statements that further clarify issues are from multiple sources including Open File documents, government documents, Internet accessible data and are listed under Resources Consulted found at the end of the geographic summary. Only direct quotes or facts are cited. General information from multiple sources and data from Internet websites are not specifically cited.

The American Geographical Society (AGS) publishes a contemporary magazine, Focus, which has geographic articles accompanied by pictorial essays and graphics. The AGS has donated a Focus issue with an article about cranberry bogs in Massachusetts for use with this WETMAAP site.

Note: The Geographic Summary is a compilation of information from existing sources and is intended to provide a brief synopsis concentrating on wetland changes in the Weweantic River area and . It is not meant to be an in-depth treatise on the geography and background of the area.

The Weweantic River WETMAAP site is located west of Carver, Massachusetts, which produces one-quarter of the states cranberry harvest. Cranberry bogs exist in several area of the United States, but a dominant area of cranberry production is in wetlands of Massachusetts specifically in the Buzzards Bay watershed area. The site is within the Buzzards Bay watershed. Figure 1 shows the extent of land area of the Buzzards Bay Project Natural Estuary Program and the distribution of cranberry bogs within the estuary. (Red indicates the cranberry bogs.) Approximately one-fifth of the U.S. annual cranberry harvest is produced within the watershed of Buzzards Bay.

Source: Buzzards Bay Project, National Estuary Program

(www.buzzardsbay.org/craninfo.htm)

Figure 1. Distribution of Cranberry Bogs in the Buzzards Bay Watershed

Economic Impact of Cranberry Production:Cranberry bogs have long been an important part of Massachusetts' culture, economy, and history. Cranberry production in Massachusetts is centered around Cape Cod, Barnstable and Plymouth counties being the two biggest producers. The town of Carver produces about 25% of Massachusetts’ cranberry harvest and is also the headquarter city of the Oceanspray cranberry cooperative.

In 1996, cranberry production in Massachusetts exceeded $117 million in product value, accounted for 35% of world production, resulting in 5,500 jobs, and $2 million in payroll to Commonwealth residents. Cranberry production represents the third largest single agricultural commodity in Massachusetts, following greenhouse plants and dairy farms. Massachusetts growers have a higher cost of production and average yields below the national average.

Cranberry prices increased steadily and dramatically between 1985 and 1998. This resulted in an increased acreage of bogs in Massachusetts. In 1999, prices collapsed, reaching a low of $11 per barrel for some independent growers. The market has not yet recovered. Prices are below production costs for some farmers and acres of cranberry bogs in active production have declined. Figure 2 shows cranberry prices and average production per acre, while Figure 3 shows the acres in production. There is a decline in acreage after 2001 and an increase in acreage for 2003-04.

Source: Buzzards Bay Project, National Estuary Program (www.buzzardsbay.org/craninfo.htm).

Data for graphs from: USDA NASS Statistics.

Figure 2. Average Massachusetts Cranberry Prices and Production per Acre.

Source: Buzzards Bay Project, National Estuary Program (www.buzzardsbay.org/craninfo.htm).

Data for graphs

from: USDA NASS Statistics.

Figure 3. Total Massachusetts Cranberry Acres.

Massachusetts bogs, in general, are typically small, averaging only 20 acres per bog. In contrast to bogs in Wisconsin, Massachusetts bogs tend to conform to the hilly terrain. Massachusetts growers also use native berry varieties whereas the Wisconsin growers are more likely to use hybrids that give higher yields per acre. Massachusetts growers are relying on producing higher yields to remain competitive in the market.

By 1975 much of Massachusetts cranberry bog areas had reached capacity, that is, there was little space left for new bog development. When prices were high in the mid 1980s, and prices continued to increase in the 1990s, farmers revived old bogs that were left dormant. Cranberry prices collapsed in 1999, and currently prices continue to decline (www.buzardsbay.org).

According to Tim White (2003), a wetland scientist with the Massachusetts Restoration Project, the number of acres restored back to wetlands is virtually none, with the exception of about 30 or 40 acres, but this is considered an insignificant amount compared to the total acreage of land in cranberry bogs.

Bogs are waterlogged peatlands in old lake basins, on flat uplands, along sluggish streams, or other depressions in the landscape. They form when the rate of peat accumulation is greater than the rate of decomposition as a result of climactic conditions.

Bogs are characterized by spongy peat deposits, acidic waters, and a floor covered by a thick carpet of sphagnum moss. Bogs receive all or most of their water from precipitation rather than from runoff, groundwater, or streams. As a result, bogs are low in the nutrients needed for plant growth, a condition that is enhanced by acid forming peat mosses. Vegetation is woody or herbaceous, or both. Typical plants are heath shrubs, sphagnum moss, and sedges. Bogs do not support large populations of wildlife, but they do provide important habitat for moose, deer, black bear, lynx, fishers, snowshoe hare, otter, and mink. Migratory birds use bogs on their flight paths.

Bogs and fens are often confused. A fen is a type of peatland with nutrient-rich waters and is found primarily along the edges of lakes and rivers or the perimeters of bogs. Fens are dominated by herbaceous plants rather than the Sphagnum moss characteristic of bogs. Fens receive nutrients and minerals from groundwater, and they tend to be less acidic that bogs. The vegetation consists predominantly of sedges, grasses, rushes and mosses, with some shrubs and, at times a sparse tree layer.

Bogs in the United States are mostly found in the glaciated northeast and Great Lakes regions (northern bogs), but also in the southeast (pocosins). Their acreage declined historically, as they were drained to be used as cropland, and mined for their peat which was used as a fuel and a soil conditioner. Recently, bogs have been recognized for their role in regulating the global climate by storing large amounts of carbon in peat deposits. Bogs are unique communities that can be destroyed in a matter of days, but require hundreds, if not thousands, of years to form naturally.

Bogs serve an important ecological function in preventing downstream flooding by absorbing precipitation. Bogs generally have no significant water inflow or outflow, but some bogs can act as headwaters, recharge groundwater, or help maintain the pressure of the water table. This is uncommon due to the impermeable nature of the peat layer. Bogs support some of the most interesting plants in the United States including cranberries, and provide habitat to animals threatened by human encroachment.

The Massachusetts Wetland Protection Act regulates activities that alter the functions of wetlands including cranberry beds. Cranberry beds meet the definition of Wetlands as defined by the Act. Cranberry bogs and the water storage areas maintained by growers contribute significantly to flood control, prevention of pollution and storm damage, and ground water recharge.

Bogs and Cranberry Cultivation

Cranberry bogs must have the following three essential features in order to successfully produce cranberries, (1) an ample supply of good quality fresh water, (2) excellent drainage from the beds achieved by having appropriate sand and good ditching, and (3) soils with the ability to hold a flood water to cover the vines for winter protection and water harvesting. Current cranberry cultivation is similar to early cranberry production, but management practices and technology permit greater productivity. Pressure to preserve wetlands has forced new cranberry development into upland settings, which has been developed and designed to mimic the natural bog setting. These settings range from sandy sites with a naturally high water table, to impermeable clay based sites with no natural water table and anything in between.

The American cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, is a native wetland plant that requires well-drained soils during the growing season. Cranberry cultivation is a water intensive operation. Bogs are flooded from late December through mid-March (when the cranberry vines are dormant) to protect the plants from dessication and winter injury. Bogs may be reflooded later in the spring for weed and pest control (Cape Cod Cranberry Growers' Association).

The American or large cranberry, is the only species of the wild berry that is cultivated commercially. It is a small evergreen shrub that thrives in the acidic, nutrient-poor soils of peatlands. The American cranberry grows wild in wetlands from Newfoundland and the Canadian Maritime provinces to Ontario; from Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan to New Jersey, Long Island and Southeastern Massachusetts. In the United States, five states produce the nation's cranberries: Massachusetts, New Jersey, Wisconsin -- where the berry is native; and Washington and Oregon produce most of the cranberries in the United States (www.cranberries.org).

Boggs are characterized by evergreen shrubs of the heath family (Ericaceae), such as Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), Labrador tea (Ledum groenlandicum), Bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla) and Small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos).

Four specific issues related to cranberry production and cultivation: (1) groundwater withdrawal; (2) nutrient loading and non-point pollution; (3) water quality; and (4) commercial and urban development.

White, Tim. 2003. Personal Communication. Massachusetts Wetland Restoration Project, Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Boston Massachusetts (10/07/03).

http://www.umass.edu/cranberry/

http://www.buzzardsbay.org (active as

of October 20, 2004)

http://www.geocities.com/cranberrybogs/gazette_081601.html

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1998/uswetlan/type8.htm

http://www.epa.gov/owow/wetlands/types/bog.html

http://h2osparc.wq.ncsu.edu/info/wetlands/types3.html#gr

http://site.www.umb.edu/conne/marsha/cranintro.html

http://www.cranberries.org (Cape Cod

Cranberry Association)