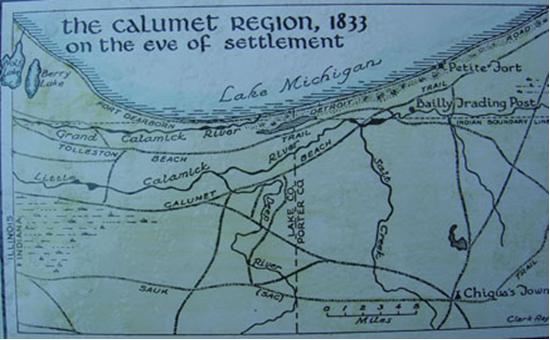

Figure 1. Lake Michigan shoreline, 1833.

Indiana Dunes

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

Summary information for the Indiana Dunes site is a compilation of existing sources and selected documents, Internet accessible data, which are referenced by section. The Geographic Summary is intended to provide a brief synopsis concentrating on Indiana Dunes, wetlands, and related features. It is not meant to be an in-depth treatise on the geography and background of the area.

Brief History of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

Formation of Lake and Sand Dunes

Formation of Bogs, Marshes, and Forests

Topography: General Description

Climate: Rainfall and Temperature Patterns

Preeminent Invasive Plant Species in the Indiana Dunes

General Information for Cowles Bog

Specific Vegetation for Cowles Bog

Loss of Open Water in Cowles Bog

Indiana Dunes

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

Brief History of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

The legislation that authorized Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 1966 resulted from a movement that began in 1899. Henry Cowles, a botanist from the University of Chicago, published an article entitled "Ecological Relations of the Vegetation on Sand Dunes of Lake Michigan," in the Botanical Gazette in 1899 that established Cowles as the "father of plant ecology" in North America and brought international attention to the intricate ecosystems existing on the dunes. Industry exploited the dunes for their own profit, with no view towards protecting the environment of the area.

The Prairie Club was formed in 1908 in Chicago to urge the protection of the Indiana Dunes. The forerunner of the current park administration was borne out of the Prairie Club's National Dunes Park Association. On October 30, 1916, only a month after the National Park Service was established, hearings were held on the political viability of a potential Sand Dunes National Park. Support ran high until the coming of the First World War, when priorities switched to first and foremost winning the war. After the war came the Great Depression, once again demanding higher priority from politicians than the preservation of the Dunes.

Nonetheless, support continued. Indiana Dunes State Park was created in 1923 by an act of the Indiana General Assembly, and opened to the public in 1926. Three miles and 2,182 acres of Indiana's lakefront were preserved, but most of the dunes remained in private hands. The push for a national lakeshore continued. The Save the Dunes Council was established by local activists to purchase various sites in the area, their first purchase being 56 acres in Porter County known as Cowles Bog.

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was established by an act of Congress in 1966 and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The initial authorization for the park granted 8,330 acres but that was enlarged over time with four expansion bills (in 1976, 1980, 1986, and 1992) to become the current size of over 15,000 acres and twenty-five miles of waterfront. Figure 1 represents the region pre-settlement.

sources:

Figure 1. Lake Michigan shoreline, 1833.

Formation of Lake and Sand Dunes

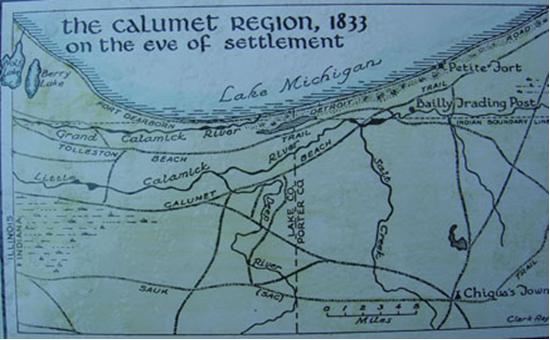

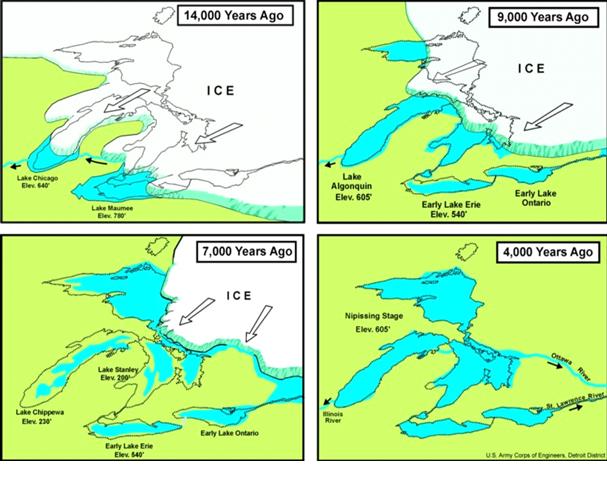

The Indiana Dunes were created in several stages. The Great Lakes were largely covered during the Ice Age, about 14,000 years ago. The only sections of the Great Lakes free from glaciations were Lake Chicago, extending past the current shoreline of southern Lake Michigan; and Lake Maumee, extending past the current shoreline of western Lake Erie.

Figure 2. The development of the Great Lakes, courtesy United States Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District.

The shoreline experienced the erosive effects of any standard freshwater system at frigid latitudes, but the chief contributor to the sand buildup was the glaciers. After shoveling out and eroding the earth for hundreds of miles on its journey south, the Wisconsin Glacier amassed a pile of detritus that was moved south by wind and spring melts. Much of this detritus was deposited in the Indiana Dunes area.

Further erosion and deposition continued as the levels of Lake Chicago receded to near-modern levels around 9,000 years ago, continued to shrink 7,000 years ago, and then rebounded to the current levels 4,000 years ago. Waves largely hit the coastline at an angle, establishing longshore currents favorable to deposition and littoral drift. Wind picked up sand from the north and west and depositing it on the Indiana shore. The sand was and is caught in the vegetation, and the process continues to this day.

Formation of Bogs, Marshes, and Forests

Bogs and marshes were created by the melting glaciers, when the meltwater found no outlet to Lake Michigan or any other body of water. Cowles Bog and Pinhook Bog were formed in this manner. Slowly, as vegetation grows in the bog, dies, and decays, the wetland is filled in and with vegetation growth including tress.

sources:

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: http://www.in.gov/dnr/

City of Chicago Park District: http://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com

National Park Service: http://www.nps.gov

Great Lakes Commission: http://www.glc.org

Topography: General Description

Strong winds from the north and west have sculptured a nationally famous dunescape along the Indiana shore of Lake Michigan. Inland from the water’s edge, the first evidence of the wind's effect on shifting sands is the where the base of the dunes meet the more level lakeshore. Beach grass, with its spreading underground root system, establishes little islands of cover in the wind-blown sand. Here and there small mats of bearberry (kinnikinnick), a procumbent arctic evergreen shrub, add stability to the soil. With increases in elevation, sumac, sand cherry, cottonwood, and prostrate juniper gradually take over. There are also a few isolated stands of jack pine on these lakeward slopes.

This foredune area is characterized by a series of hills and swales. Mt. Tom, at 186 feet above the lake, is the highest of these ridge tops. Wind erosion has cut depressions, called blowouts, through these ridges. The three largest of these blowouts, Beach House, Furnessville, and Big Blowout, extend into the interdunes area of hills, pockets, and troughs. Big Blowout has uncovered an area of dead tree trunks known as the Tree Graveyard. This area was once a white pine forest before shifting sands buried it. Because sand is still unstable in the interdunes, vegetation here resembles that found on the foredunes.

The backdune area begins on the leeward slopes of active blowouts or on protected ridges. Tops and upper leeward slopes of the backdunes are forested with nearly pure stands of black oak, mixed with a few white oaks and stunted sassafras. Thick stands of blueberry, bracken fern, and greenbrier are found in the understory.

South of the dunes is a wetland area, composed of marsh, shrub shrub, and wetland forest. This large area is drained by Dunes Creek. Between the dunes and this wetland is a strip of sandy flats with greater organic matter. One sheltered cove on these flats has native white pines associated with oaks, tulip, white ash, and basswood.

From the wetland, there is a gradual upslope toward the park’s southern boundary. This slope is one of the shorelines of prehistoric Lake Chicago.

source:

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: http://www.in.gov/dnr/

Climate: Rainfall and Temperature Patterns

The Indiana Dunes have a humid continental climate with strongly marked seasons. Winters are often cold, sometimes bitterly so. The transition from cold to hot weather can produce an active spring with thunderstorms and tornadoes. Oppressive humidity and high temperatures arrive in summer. Autumn has lower humidity than the other seasons, and mostly sunny skies.

The Indiana Dunes' location within the continent highly determines this cycle of climate. The air mass of the Gulf of Mexico is a major player in the climate. Southerly winds from the Gulf region transport warm, moisture laden air into the area. The warm moist air collides with continental polar air brought southward by the jet stream from central and western Canada. A third air mass source found in Indiana originates from the Pacific Ocean. Because of the orographic obstruction posed by the Rocky Mountains, however, this third source arrives less frequently in the state.

The effect of Lake Michigan on the climate of the Dunes is most important and this effect is most pronounced just inland from the Lake Michigan shore and diminishes rapidly with distance. Cold air passing over the warmer lake water induces precipitation in the lee of Lake Michigan in autumn and winter. As a result of this phenomenon, heavy winter precipitation, especially snowfall, can extend eastward from Gary inland to as far as Elkhart. Lake-related snowfall and cloudiness can extend to central Indiana in winter, driven by strong northwesterly winds. In the spring, daily maximum temperatures decrease northward in northern Indiana because of the cooling effect of the Lake. Average daily minimum temperatures in autumn are higher by the Dunes near the warmer lake surface than farther south.

A winter may be unusually cold or a summer cool if the influence of polar air is persistent. Similarly, a summer may be unusually warm or a winter mild if air of tropical origin predominates. The interaction between these two air masses of contrasting temperature, humidity, and density favors the development of low pressure centers that move generally eastward and frequently pass over or close to the state, resulting in abundant rainfall. These systems are least active in midsummer and during this season frequently pass north of the Dunes.

Weather changes occur every few days as surges of polar air move southward or tropical air northward. These changes are more frequent and pronounced in winter than in summer.

sources:

Indiana State Climate Office, Purdue University: http://www.iclimate.org

Country Studies/Area Handbook Series, U.S. Department of the Army, 1986-1998

http://www.countrystudies.us

The national lakeshore provides habitat for approximately 1,130 native vascular plants, including the federally threatened Pitcher’s thistle. The lakeshore is home to populations of thirty percent of Indiana’s listed rare, threatened, endangered, and special concern plant species. Shaped by glacial events and changing climates, the dunes landscape contains disjunct flora representative of eastern deciduous forests, boreal forest remnants, and species with Atlantic coast affinities. In addition, the national lakeshore is part of the upper- and eastern-most limits of the tallgrass prairie peninsula and supports high quality remnants of this ever-diminishing vegetation type. The presence of many unique dune and wetland plant community types has led to a long history of botanical exploration and research.

Preeminent Invasive Plant Species in the Indiana Dunes

Hybrid cattail

(Typha glauca) is a cross between the native broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia) and the invasive narrowleaf cattail (Typha angustifolia). It can thrive in the native environs of both of its parents, and even more besides-making it an extremely dangerous plant to native vegetation. It has been prioritized for destruction by the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. [Note: cattail is a dominant problem and concern for the region.]

Purple loosestrife

Invades wetlands in northern Indiana, forming pure stands that choke out native vegetation. This eliminates food and cover for many wildlife species, which are dependent on a diverse mixture of native species to survive.

Bush honeysuckles

Grow so densely they shade out everything on the forest floor, often leaving nothing but bare dirt. This means a great reduction in the food and cover available for birds and other animals. Some species release chemicals into the soil to inhibit other plant growth, effectively poisoning the soil. Bush honeysuckles are found throughout the state, but are particularly invasive in central and northern Indiana.

Reed canary grass

Widely planted for forage and erosion control, has taken over large areas of both open and forested wetlands throughout Indiana. It forms monocultures by out-competing all the native wetland plant species. There may

be native strains in the state; however, there is no reliable way to tell the native from the non-native strains.

Autumn olive

Often planted for wildlife food and cover in the past, can quickly take over open areas, eliminating all other species. Such monocultures actually reduce the variety and amount of wildlife food available. It is now found throughout Indiana.

Common reed

Grows in open wetland habitats and ditches primarily in northern Indiana. It can create pure, impenetrable stands, excluding all other wetland plants. Some populations are not invasive and may be native; however, there is no reliable method to tell the two apart.

Garlic mustard Can grow in dense stands covering many acres of forest understory. Now found throughout Indiana, it is a particular threat to spring wildflowers, overtopping and shading them out. Compared to the diversity of plants it eliminates, it provides little food for wildlife

Oriental bittersweet

Occurs throughout Indiana and can overrun natural vegetation, forming nearly pure stands in forests. It can strangle shrubs and small trees, and weaken mature trees by girdling the trunk and weighting the crown. There is some evidence that it can hybridize with American bittersweet, thus threatening the genetic integrity of the native species.

Common and glossy buckthorns

occur in a wide variety of habitats in northern Indiana and spread quickly through natural areas by seed. They take over the understory and eliminate the diversity of native plants important to wildlife.

sources:

Indiana Native Plant and Wildflower Society: http://www.inpaws.org

COWLES BOG

Vegetation within Indiana Dunes National lakeshore helps define habitat types such as rivers and streams, bogs, bottomland (floodplain), dune complex, foredune, interdune, and backdune complexes, marsh complex, mesophytic forest and prairies, panne, savanna complex and swap complex.

Cowles Bog, part of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, is a remnant of the marsh system that once stretched from where the city of Gary is today all the way to Michigan City. Most of these wetlands were filled in years ago for the massive industries established in northern Indiana. But several spectacular sites-including Cowles Bog-have been preserved and are now administered by the National Park Service.

The wetlands of Cowles Bog are home to a variety of salamanders and other herpes; a large chorus of frogs croaks all spring and summer. The area's many habitats attract a great variety of birds, including Virginia rails, green and great blue herons, Eastern wood-pewees, and several species of hawks. Fall and spring migrations bring an even wider variety.

sources:

Indiana Native Plant and Wildflower Society: http://www.inpaws.org

National Park Service:

http://www.nps.gov

Wilhelm, Gerould S. 1990 Special Vegetation of the Indiana Dunes National

Lakeshore. The Morton Arboretum: Lisle, Illinois. January 1990.

Specific Vegetation for Cowles Bog

The Indiana Dunes Marsh Complex includes a fen, a marsh, and a wet-prairie/sedge meadow. Cowles Bog is world renowned as a classic ecological area. The core of Cowles Bog is a marsh surrounding a small fen. A fen is defined as having a basic (high pH) substrate saturated by mineral rich flowing ground water. The weeded portion in a fen is referred to as a ‘swamp complex’ (Lisle 1990). A bog is a stagnate body of [acidic] water with an in-growth of water-tolerant vegetation. Because Cowles Bog has flowing ground water throughout the March-September growing season, it is currently considered a fen.

Vegetation is varied in the Cowles Bog and adjacent areas of backdunes (black oak), interdunes (black oak red maple forest, with damp-loving yellow and paper birches), and foredunes (cinnamon ferns). There are stand of tamaracks and white pines grows on a floating mat of peat moss. The dominant vegetation in Cowles Bog is Typha ssp (cattail), which is of considerable concern for ecologist, botanists, and wetlands specialists. Specific reasons for the overabundant growth and continued increase in cattails are “unstable water levels and prolonged lack of fire” (Wilhelm 1990, 31). Other stressors include landscape alterations, chemical inputs, biological pollutants, lumbering, hydrological alterations, and haying.

Cowles Bog includes the following plants*:

Open Areas:

Bidens coronata tenuiloba

Pedicularis lanceolat

Campula aparinoides

Potentilla palustris

Dryopteris thelypteris pubescens

Rhamnus alnifolia

Galium obtusum

Salix glaucophylloides glaucophlla

Muhlenbergia glomerata

Scripus acutus

| Wooded Areas: | |

|---|---|

| Caltha palustris | Pedicularis lanceolata |

| Chelone glabra | Rhus vernix |

| Circuta maculate | Solidago patula |

| Fraxinus nigra | Symplocarpus foetidus |

| Larix lacricina | Thuja occidentals |

| Marsh Areas (rhizomatous perennials): | |

|---|---|

| Carex aquatillis altior | Carex lasiocarpa americana |

| Carex comosa | Carex sartwelii |

| Carex haydenii | Carex stricta |

| Carex lacustris | Scripus acutus |

| Carex languginosa | Scripus validus creber |

* Modified from Wilhelm, Gerould S. 1990.

Special Vegetation of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

The Morton Arboretum: Lisle, Illinois. January 1990. p. 30-31.

Cowles Bog represents 80 hectares of the westernmost extent of the Great Marsh, including the graminoid fen known as Cowles Bog, degraded marsh, and forested wetlands. Cattail (Typha spp.), Common Reed (Phragmites australis), and shrubs that displaced the unusual plant communities present during the early twentieth century. Less than one hectare of sedge meadow remains today, compared to 56.4 hectares in 1938.

Scientists of the National Lakeshore recognize that Cowles in need of resuscitation, and they also recognize the intense undertaking necessary to recover some portion of the integrity of the original ecosystem. A full restoration of Cowles bog demands work on the entirety of the headwaters of Dunes Creek. A minimum of ten years will be necessary to implement a plant community reversal. The National Lakeshore, in partnership with the US Geological Survey, the Nature Conservancy and other institutions (Iowa State University, North Carolina State University, the Wetlands Initiative) received a three-year grant entitled Restore the Biological Resources of the Cowles Bog Wetland Complex: Phase I-Inventory. Funding was awarded through the National Park Service’s Natural Resource Preservation Program.

An inventory of present-day resources at Cowles Bog area and an investigation of the best methods for cattail eradication will provide data for developing a guide for restoration work. Data will be collected on surface and ground water, water chemistry, soil chemistry, seedbank composition, and plant communities levels. Since drowning the cattail and prescribed burns are not feasible, three methods of herbicide application will be explored. Results from these investigations will be used to develop restoration and management guidelines for the next phases of restoring and managing the Bog.

sources:

National Park Service http://www.nps.gov

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore is partnering with community groups to restore the Cowles Bog wetland complex which is a mosaic of marsh, forest, and graminoid fen in the westernmost part of the Great Marsh at the Indiana Dunes. Over the past 18 years, shrubs, hybrid cattail, and common reed have expanded throughout the Cowles Bog.

Indiana's only native white cedar population is found here, but deer browsing has limited cedar reproduction. As part of the restoration project, the Friends of Indiana Dunes have helped propagate white cedars from collected cuttings.

Over the past two years, volunteers from the Northwest Indiana Chapter of The Nature Conservancy have applied herbicide to cattails on a portion of Cowles Bog known as The Mound, as well as surrounding wetlands. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore estimates it could take 15 to 20 years and cost nearly two million dollars to complete the restoration project.

sources:

National Park Service: http://www.nps.gov

Loss of Open Water in Cowles Bog

Several issues related to bringing about a loss of open water (as represented by acres of sedge meadow) in Cowles Bog:

Methods for correcting loss of open water include:

With the decline of the steel industry, as well as stricter government standards, pollutants are less of a problem, although the nearness of the mills to the Dunes exacerbates what problem is left.

sources:Cattail modify the physical environment and the cumulative impacts of graminoid affect fen vegetation. Cattails pose the most threat for the restoration of Cowles Bog. A series of best practices are in place to help restore Cowls Bog including a concerted effort to eradicate cattail in areas where they have changed habitat and invaded bogs is underway in for Cowels Bog.

The most damaging Cowles Bog, despite its name, is a graminoid fen. It was declared a natural national landmark in 1965 and no longer holds that distinction. Instead, because of anthropogenic stressors, the vegetation has been compromised. and such fens are big on the list as conservation target. A 1980s study of Cowles Bog and adjacent wetlands are