Fort Clatsop Background Information

The Lewis and Clark Expedition

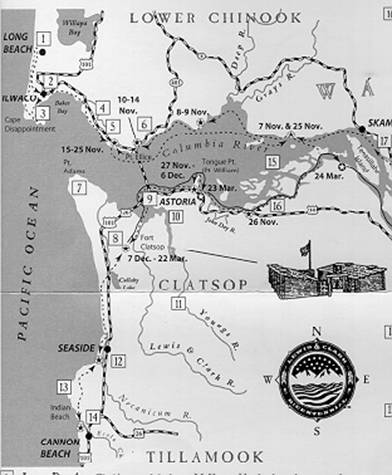

Figure 2.3: Louis and Clark Expedition Route

Lewis and Clarks’ Choice of Location

Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop

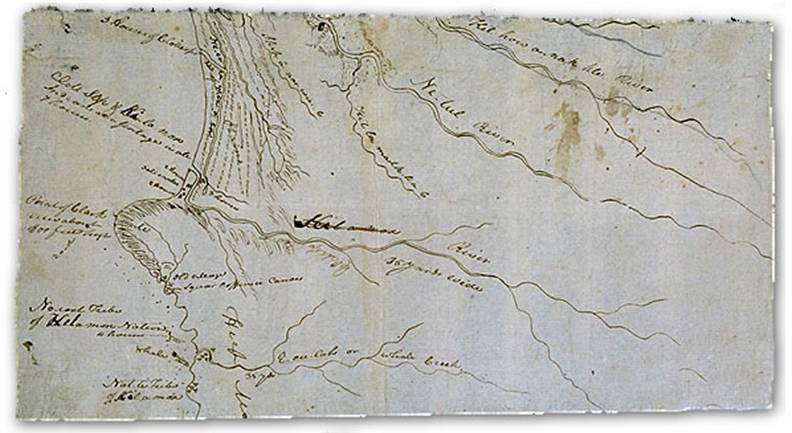

Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works

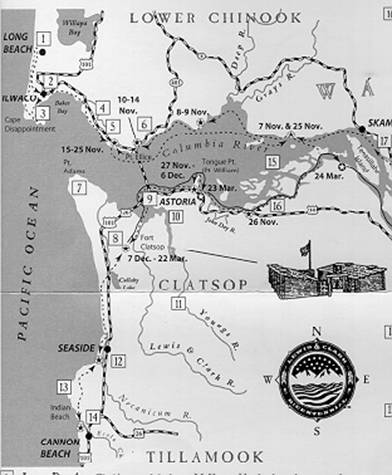

Figure 2.4: William Clark’s drawing of area near Seaside and salt works

Lewis and Clark’s Descriptions of the Fort Clatsop Area

Lewis and Clark’s Descriptions and the Contemporary Environment

Background Information

Fort Clatsop

Oregon

The Pacific Northwest Coast is famous for its lush temperate rain forests and rugged, hilly terrain. The Columbia River is the fourth largest river system in the United States, and its estuary at the Pacific Ocean supports a variety of wildlife and numerous plant species (Figure 2.1).

Source: Plants of Fort Clatsop, From the Journals of Lewis and Clark, Fort Clatsop Historical Association, 1989, Scott Eckberg, Series Editor.

Figure 2.1: The

Columbia River Estuary

The dashed line along the southern shore of the estuary is the route of the

expedition. The route continues south to Seaside, the location of the salt

works.

Within geological time, the Columbia River estuary is a recent feature. The Columbia River once flowed through Oregon-- south of its present course, emptying into the ocean near present-day Yaquina Bay, which is a river-dominated estuary with mostly freshwater flow and few tidelands.

A comparison of Lewis and Clark’s topographic observations with current wetlands and surroundings suggest that vegetation and climate patterns have remained constant. Yet, while some changes continue, including urban expansion and agricultural and commercial development, much of the landscape has been altered since Lewis and Clark’s original observations.

Fort Clatsop is located in the Pacific Northwest Coast Region of the United States, about five miles southwest of Astoria, Oregon, on the Colombia River Estuary (Figure 2.2). To the north of Fort Clatsop are the Columbia River and Youngs Bay. To the south and the east is the Coastal Range, and to the west, the Pacific Ocean.

Lewis and Clark built their winter encampment on the Lewis and Clark River, which flows into Youngs Bay, on the south side of the Columbia River. The fort is situated on “high-ground,” an area about 30 feet above sea level.

The Pacific Ocean is a dominant factor in the climate patterns of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The Pacific Ocean moderates air temperature that contributes to warm, wet winters and cool, wet summers. The mean annual precipitation for Astoria, Oregon is 66.42 inches; however, there are some areas along the Pacific Northwest Coast that receive up to 197 inches of rain per year.

Source: Plants of Fort Clatsop, From the Journals of Lewis and Clark, Fort Clatsop Historical Association, 1989, Scott Eckberg, Series Editor

Figure 2.2: Location of Fort Clatsop National Memorial

The decision to cross to the south side of the Columbia River (near modern-day Astoria) to build winter quarters was based on a majority vote by the expedition members, including the slave York, and Sacagawea (Timeline, www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html).

In addition to rain, the area is often covered with dense fog. An observation by Patrick Gass, an expedition member, emphasizes the constant climate and the dismal perception of the region:

Again we had a wet stormy day, ... There is more wet weather on this coast, then I ever knew in any other place; during the month we have had but 3 fair days; and there is no prospect of a change (December 05, 1805)

Journals, Lewis and Clark Expedition, www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html

The Fort Clatsop area has an abundant amount of vegetation as illustrated in the table of common vegetation (Table 1).

Table 1

Common Wetland Vegetation of Fort Clatsop *

and Use at the time of Lewis and Clark Encampment

| Type | Common Name | Generic Name | Use* * |

| Upland Forest | Douglas Fir | Pseudotsuga menziesii | boiled pitch used as food; springs needles boiled for tea |

| Grand Fir | Abies grandis | wood used for firewood and tools | |

| Western Red Cedar | Thuja plicata | wood used for boxes, tools, canoes, clothing, mats, twine, and rope | |

| Western Hemlock | Tsuga heterophylla | new growth used as tea; bark for dye; pitch used to cure chapping and sunburn prevention | |

| Sitka Spruce | Picea sitchensis | roots used for rope and twine; pitch used for caulking; saplings used for snares; wood used for tools | |

| Upland | Red Alder | Alnus rubra | wood used for bowls, spoons, and smoking salmon; bark used for dye Scrub-shrub and tea (relief of aching bones) |

| Western Crabapple | Phyrus fusca | fruit stored for later use; bark either chewed or used as tea for gastrointestinal disorders | |

| Bigleaf Maple | Acer macrophyllum | ||

| Wetland | Thimbleberry | Rubus parviflorus | berries eaten fresh in spring; young shoots peeled and eaten |

| Scrub-shrub | Ocean Spray | Holodiscus | discolor flowers used as cure for diarrhea; twigs used for arrow shafts |

| Red Elderberry | Sambucus racemosa | steamed and stored berries for later use; bark boiled and used as a poultice | |

| Coast Black Gooseberry | Ribes divaricatum | porridge of cooked gooseberries used for fever and malaria | |

| Ninebark | Physocarpus | fruit eaten by Native children | |

| Salal | Gaultheria shallon | berries highly praised by Natives | |

| Black Twinberry | |||

| Fresh Marsh | Cattail | Typha latifola | roots eaten by Natives |

| Wapato | Sagittaria latifolia | root used for food by Natives | |

| Skunk Cabbage | Lysichiton | leaves edible after two or three boiling | |

| Cow Parsnip | Heracleum lanatum | burnt stalks used as substitute for salt | |

| Horsetail | Equisetum telmateia | roots and stalks eaten when cooked with oil | |

| Ferns | Bracken Fern | Pteridium aquilinum | roots roasted, peeled, and eaten; frond laid on fish cleaning boards |

| Sword Fern | Polystichum munitum | root tubers source of food | |

| Licorice Fern | Polypodium glycyrrhiza | rhizomes roasted and peeled used to help cough | |

| Deer Fern | Blechnum spicant | eaten to relieve thirst; chewed leaves used as a medicine | |

| Lady fern | Athyrium filix-femina | young shoots steamed and eaten | |

| Salt Marsh | Common Rush | Juncus effuses | |

| Tall Bulrush | Scirpus californicus | ||

| Smooth Cordgrass | Spartina alternifolra | ||

* Nancy Enid, Fort Clatsop National Monument, verified and corrected species, common, and generic names.

** Native use and use by the Lewis and Clark Expedition at Fort Clatsop are from Plants of Fort Clatsop, From the Journals of Lewis and Clark, Fort Clatsop Historical Association, 1989, Scott Eckberg, Series Editor.

The Pacific Northwest Coast has extremely dense and fertile forests because of the large amount of precipitation and a nutrient rich soil. The dominant forest around Fort Clatsop is maritime rainforest (a type of temperate rainforest). Western hemlock and Douglas-fur are dominant trees with Douglas-fur occupying the drier areas. The forest contains a complex structure of canopy layers, large variety of trees, epiphytes (plants coexisting on top of other plants such as hanging lichens, mosses and ferns) and thick shrubs.

Most grasslands are around the Willamette Valley and north to Puget Sound-Strait. Grasslands flourish along the south end of mountains, and are maintained by cattle grazing and fire. Before European settlement of the region, the dominant grassland plants were native perennial grasses such as fireweed, lilies, and various shrubs. European settlers brought Eurasian annuals and weedy grasses that now dominate the landscape.

The wetlands in the Fort Clatsop area are of two types, estuarine and freshwater. Esturaine wetlands fall into four categories: rocky shores, which are more common and support little vegetation due to wind and exposure to salt water; shingle beach wetlands composed of large gravel and allow for the growth of hardy plants such as searocket and dunegrass; sandy beaches and flats located in small areas behind headlands of uncovered outer coastal areas and are the least common type; and tidal saltmarsh that support the largest variety of vegetation due to abundant sediment nutrients.

Freshwater wetlands fall into three categories: bogs, distinguished by stagnant water from rain or snow melt, and are very acidic; and fens and marshes, characterized by less acidity and greater amounts of vegetation. Freshwater marsh is the most dominant wetland for the Fort Clatsop area.

The Fort Clatsop National Memorial area has three dominant wetland systems, palustrine, estuarine, and riverine, which comprise approximately 75 acres or one-third of the park’s ecosystem. The dominant tree species is red alder (Alnus rubra), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and western red cedar (Thuja plicata). Western hemlock and western red cedar are slowly replacing the red alder. Another common tree species is the Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), also known as a “gap-phase” tree, which means it fills in open gaps in between the dominate tree communities. The tree species of Fort Clatsop provide a dense canopy above the wetland areas and often hide the underlying wetland community.

The understory consists of vegetation from several classes of plants such as lichens, bryophytes (mosses, liverworts), ferns, and vascular plants, which include gymnosperms, monocot, and dicot plant species. Fungi also grow in the Fort Clatsop area, but they are not as abundant and are of a smaller variety than other vegetation.

Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have inhabited the Fort Clatsop region for ten to fourteen thousand years. The early residents subsisted largely on marine life, but also relied on other local resources. They modified the landscape by cutting forests to create meadows, which encouraged growth of vegetation such as berries, nuts, and root vegetables. The meadows also attracted deer and other game animals.

The Amerindians lived in small groups along the coastline or river shores, and they displayed a variety of cultures and languages. The favorable climate meant an area rich in resources, and allowed the local Amerindians to lead a sedentary lifestyle without relying on agriculture. In the spring and summer, they harvested Makah, Quinault, and Quileute whales, porpoises, seals, halibut, salmon, and cod from the Pacific Ocean. Lewis and Clark observed the Clastop Indians conducting whaling expeditions in the Columbia River Estuary. Most often the Amerindians killed whales that were beached or drifted too close to shore, although some were speared in the water. The natives also fished extensively for such species as flounder, salmon, steelhead trout, freshwater trout, and red charr. In addition, these indigenous peoples hunted deer, elk, and small game, and gathered roots, berries, and nuts.

The local Amerindians utilized small cedar boats for transport along the Pacific Coast and for navigation of rivers. The boats varied in length from 16 feet for river vessels to as much as 60 feet for coastal transport. Amerindians’ huts, like their boats, were constructed of cedar and were either rectangular or square shaped. The huts were used for ceremonies in winter as well as shelter from the rainy weather common to the Pacific Northwest. The huts were14 to 20 feet wide and 20 to 60 feet long, and were occupied by several families separated by partitions.

Lewis and Clark documented Indian dress, housing types, hunting techniques, beliefs, and customs. The local natives’ clothing was made of sea otter, beaver, elk, deer, fox, and cat pelts. Beads and eagle feathers were frequently used as jewelry and to adorn clothing.

Much of the native knowledge of the region was of benefit to Lewis and Clark’s expedition, and helped them to survive the winter of 1805-06.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition

During the early nineteenth century, Napoleon was heavily involved in the exploration and land acquisition of the New World. After an embarrassing defeat in Santo Domingo, and pressure from the war he was waging in Europe, Napoleon lost interest in the Americas and focused his attention on the conflicts in Europe.

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson, then President, sent James Madison to France to negotiate a deal for the acquisition of New Orleans. To Jefferson’s delight, Napoleon wanted to end his involvement in the Americas and offered to sell the entirety of the Louisiana Territory to the United States. The territory encompassed some 880,000 square miles for the asking price of a mere fifteen million dollars.

After the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory from France, Jefferson hired Meriwether Lewis to explore and describe the territory in detail. Jefferson’s instructions were quite specific:

Your observations are to be taken with great pains and accuracy, to be entered distinctly, and intelligibly for others as well as yourself, to comprehend all the elements necessary, with the aid of the usual tables, to fix the latitude and longitude of the place which they were taken…Other objects worthy of notice will be…climate as characterized by the thermometer, by the proportion of rainy, cloudy and clear days, by lightning, hail, snow, ice by the access and recess of frost, by the winds prevailing at different seasons, the dates at which particular plants put forth or lose their flowers, or leaf, times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles or insects (Holloway: 1974, 20).

Jefferson, knowing the dangers of the expedition, asked Lewis to hire someone to take over if he should fail to complete the exploration. Lewis chose William Clark, who in turn, hired several men to aid in the expedition. The expedition party of forty-five left present-day Saint Louis on May 14, 1804, and sailed northwest on the Missouri River. The expedition spent the winter of 1804-1805 with the Mandan Indians at Fort Madison near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. In April 1805, the explorers continued west, and by November of that year, they reached the Oregon coast (Figure 2.3).

Upon finally reaching what Clark thought to be the Pacific Ocean on November

07, 1805, he expressed the general mood of the expedition, “Great joy in camp…We

are in view of the ocean…this great Pacific Ocean;” but the miserably wet

weather soon dulled the joy, “O! how disagreeable is our situation during this

dreadful weather” (Hawke: 1980, 223,224).

Source: http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_map.html

Figure 2.3: Lewis and Clark Expedition Route

Red represents the expedition route west beginning in St. Louis, Missouri and continuing to Fort Clatsop, Oregon. Blue is the return trip.

Lewis and Clark’s Choice of Location

Lewis and Clark realized that they must build a permanent encampment if they were to survive the Pacific Northwest wet winter, and prepare for the return journey to St. Louis. Lewis and Clark spent two weeks deliberating the location of the encampment, finally settling on a site on the south shore of the Columbia River away from the damp, wind swept coastline of the Pacific Ocean. The local Amerindian tribe, the Clatsops, told the explorers about an elk herd that grazed nearby; the elk became the camp’s main food source. The terrain on the south side of the river was less marshy than the northern side and provided adequate opportunity for defense if the need arose. In addition, proximity to the sea allowed a watch for any trading vessels at the Columbia River Estuary (gaining supplies and to send reports and findings to Washington) and for the boiling of seawater to condense salt for the journey home.

On December 7, 1805, Lewis and Clark finally settled on a specific site for Fort Clatsop, which was in a thick stand of pines two hundred yards from the Lewis and Clark River, approximately 30 feet above the highest tides. Some of the explorers began construction of the fort while others hunted and gathered food. The fort was completed just before Christmas. A December 25, 1805 journal entry by John Ordway comments on settling at the Fort, “…rainy & wet. disagreeable weather. we all moved in to our new Fort, which our officers name Fort Clatsop after the name of the Clatsop nation of Indians who live nearest to us…” (Journals, Lewis and Clark Expedition, www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html).

Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop

Lewis and Clark ran the fort like a military encampment, as evidenced by the security measures they put in place. Four guards were posted at night. The fort gates were shut at sunset or immediately after any Indians within the compound had been ‘dismissed.’ The guards had to open and then immediately shut the gates for anyone entering or leaving after nightfall. Such security measures suggest that Lewis and Clark did not feel entirely safe.

The explorers spent the winter preparing for the journey back to St. Louis. Lewis and Clark spent much of their time working on journals, maps, and documenting plant and animal specimens. The enlisted men spent much of their time hunting; in three and a half months at Fort Clatsop, they consumed 131 elk and 20 deer. Dog meat became a favored food. Elk and deer hides were used for new buckskins because their existing clothing rotted quickly in the wet climate, and to make 350 pairs of moccasins for the return journey.

The Clatsop and Chinook natives went to the fort frequently to trade or visit, often asking high prices for trade goods. Lewis and Clark’s journal entries on the Chinook and Clatsop groups provide the best, most detailed accounts of these peoples available today. For example, an excerpt from the November 23, 1805 journal entry of Joseph Whitehouse explains trade and the value placed upon items by the Clatsop:

The Indians here, set a high value on the Sea Otter skins. Our officers were very anxious to purchase a Robe made out of the Skins of two of these animals. They offered the Indians a great price in Cloths & trinkets for it; but they refused their offer, & would take nothing but beads for them. They at last offered to let them have it for 5 New blankets, which our Officers would not give them. They at last purchas'd it from them for a Belt which had a number of beads on it, which our officers procured from the Indian Woman our Interpreter, which we got at the Mandan Nation, as the Interpreter to the Snake nation; who is still with us. I mention this in Order to show the high value that they set on these Skins, which were very berautiful.

I also mention this circumstance, in order, to show the very high value, they also set on Beads.

Journals, Lewis and Clark Expedition,

www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html

Patrick Gass’ March 21, 1806 journal entry describes general characteristics of natives and compared the Clatsop with the Flathead, a tribe that the expedition encountered on its journey west:

These Indians on the coast have no horses, and very little property of any kind, except their canoes. The women are much inclined to venery, and like those on the Missouri are sold to prostitution at an easy rate. An old Chin-ook squaw frequently visited our quarters with nine girls which she kept as prostitutes. To the honour of the Flatheads, who live on the west side of the Rocky Mountains, and extend some distance down the Columbia, we must mention them as an exception; as they do not exhibit those loose feelings of carnal desire, nor appear addicted to the common customs of prostitution: and they are the only nation on the whole route where any thing like chastity is regarded.

Journals, Lewis and Clark Expedition, www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html

Lewis and Clark left Fort Clatsop on March 23, 1806, beginning their return trek to St. Louis. Joseph Whitehouse nicely sums the expedition’s experiences and final impressions of their sojourn at Fort Clatsop:

We have been at Fort Clatsop from the 7th day of December last past; and our party had lived as well, as could be expected, & can say that they never were, without 3 Meals each day, of some kind of food, either Elk meat, Roots, fish &c. notwithstanding the repeated rainey Weather, which fell (with a few days intermission) ever since, we passed the long Narrows of Columbia River, which was the 2nd of November last past. ... The fort was built in the form of an oblong Square, & the front of it facing the River, was picketed in, & had a Gate on the North & one on the South side of it. The distance from the head waters of the So. fork of the Columbia River; (Kiomenum of Lewis's River) to fort Clatsop is 994 Miles, ... & from the Mouth of the River de Bois 4134 Miles, the place from whence we took our departure, & in Latitude 46 degrtees 11 1/10 S North.

At 1 o'Clock P.M. we embarked, on board our Canoes from Fort Clatsop, on our homeward bound Voyage.

Journals, Lewis and Clark Expedition, www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_jou.html

Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works

Lewis and Clark knew they would need salt for the return journey. The easiest

way to obtain salt was by boiling seawater. Boulder furnaces 15 miles southwest

of Fort Clatsop, south of modern day Seaside, Oregon were constructed to

evaporate ocean water and producing a sea salt residue (Figure 2.4). Three

members of the party were assigned the duty of attending to the salt works, with

personnel rotated on a regular basis. The salt crew spent seven weeks boiling

seawater in five kettles, eventually extracting three and a half bushels of salt

for use at Fort Clatsop and the homeward journey.

Source: http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_map.html “Whale Drawing by William Clark” Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Figure 2.4: William Clark’s drawing of the area near present-day Seaside and the Salt Works.

Lewis and

Clark’s Descriptions of the Fort Clatsop Area

Lewis and Clark’s descriptions show a consistent pattern of rain, fog, and

wind common to the Pacific Northwest Coastal Region. In November of 1805, they

recorded twenty-four days of rain and the days without rain were foggy with

thick cloud cover. The rain continued throughout the party’s stay at Fort

Clatsop, with rain recorded every day in December. The incessant rains tapered

off in January and February, but the weather was consistently humid with fog and

thick cloud cover.

Description of

Vegetation

Among their journal entries, Lewis and Clark noted the vegetation in the Fort Clatsop area. They described several species of fern, licorice, and Wapato arrowhead (sagittaria latifolia), an edible plant found in the swamps and marshes of the region.

The intense rain and humid conditions made for lush vegetation especially

around the Colombia estuary. Lewis and Clark observed plants that commonly grow

in moist conditions: several species of ferns, the Wapato arrowhead (sagittaria

latifolia), and licorice. The Wapato arrowhead grows abundantly in swamps and

marshes. The licorice Clark described as similar to licorice cultivated in

gardens. The natives taught Lewis and Clark that when cooked properly, ferns,

Wapato and licorice could be palatable.

Wildlife

Lewis and Clark noted numerous types of animals during their stay at Fort

Clatsop. Among them was the Sharp-tailed Grouse or Prairie Hen, most likely a

subspecies of the grouse the party observed earlier along the Missouri River.

The Sage Grouse, or ‘Cock of the Plains” was a new species discovered by the

explorers. Other birds seen in the area included eagles, swans, Sandhill Cranes,

Great Blue Herons, Red-tailed Hawks, and California Condors. Elk and deer were a

common sight and the main food source for the party. Lewis and Clark also noted

rattlesnakes, the Pacific Red-sided Garter Snake, and the common garter snake.

Lewis and Clark’s Description and the Contemporary Environment

The natural environment of the northern Coast Range of Oregon has gone through tremendous human-caused changes. This is mainly because of early settlement of the area, specifically due to the attraction of the large coniferous forests for the timber industry. Some natural disturbances, such as erosion and fire, have also played a role in changing the environment.

The hydrology of the area has been affected in several ways. Water has been diverted, floodplains have been diked, and streams have been channelized For example, the floodplain of the Lewis and Clark River has had numerous dikes built to keep flood waters and saltwater from impacting the agricultural fields and urban settlements.

Many environmental changes have occurred since Lewis and Clark made their observations of the Fort Clatsop area, some changes are a result of human-induced causes and others due to natural causes.

One environmental issue is diking and filling, which originally was to provide agricultural and grazing land. The filled land is now being used for residential and commercial development. Approximately 80% of the historical wetlands in the Columbia River Estuary have been wither lost or altered.

Another issue is the loss of salmon habitat. Because of the damming of the Columbia River, the salmon can no longer reach their spawning grounds and the salmon population in the area has dropped precipitously. Attempts have been made to restore salmon and trout habitat while still maintaining tidal flood control. Lighter, aluminum tide gates, which open faster and wider, have been installed in some sloughs. This allows the fish greater mobility from one side of the gates to the other. The new tide gates improve circulation of water and lower the water’s temperature, which is beneficial to salmon and trout.

Logging is a major issue for the area and is also related to salmon decline; the fish and the forests are dependent on one another. The salmon bring nutrients inland when they spawn, allowing for the massive diversity of flora and fauna in the Pacific Northwest. Salmon require clear, cold streams for healthy spawning habitat. Clear-cut logging alongside rivers causes soil to run off into the streams, the streams then begin to warm and carry less oxygen, making them unfit for spawning. Independent of the salmon issue, logging and deforestation cause habitat fragmentation by cutting the forest into small segments with logging roads.

Conclusion

Fort Clatsop is an area rich in resources and tradition. It illustrates the idea

that the Earth is a dynamic place and is changing. Lewis and Clark’s accounts

offer a good understanding of what the area was like in the early nineteenth

century, and provide an excellent means of comparing the region to the landscape

of today.

Humans and nature have done much to alter the Columbia River Estuary. The success or failure of these efforts will have a dramatic impact on the future health of wetlands, vegetation, and wildlife.

Barbour, Micheal G., Billings, William D. 1988. North American Terrestrial Vegetation. Cambridge University Press.

Burns, Ken. “Lewis and Clark a Journey of Corps and Discovery.” In PBS Online [The Archive] S.1 2002- [cited 22 January 2002]. Available from http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/

Butler, Virginia L. “Resource Depression on the Northwest Coast of North America.” Antiquity (Summer 2000): Vol, 74 no 285 pages 649-661.

Curtis, Carlton C., Bausor, S. C. 1943. The Complete Guide to North American Trees. Greenberg Publisher Inc., New York.

“The Corps of Discovery.” 1997. National Park Service. Department of Interior &The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc.

Eckberg, Scott., editor. 1989. Plants of Fort Clatsop: From the Journals of Lewis and Clark. Fort Clatsop Historical Association.

Hawke, David Freeman. 1980 Those tremendous Mountains: The story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

Holloway, David. 1974. Lewis and Clark: and the Crosing of North America. New York: Saturday Review Press.

Peattie, Donald C. A Natural History of Western Trees. The Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 1953.

Pojar, Jim and Andy MacKinnon ed. 1994. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. British Columbia: Lone Pine Publishing.

Schwantes, Carlos A. 1989. The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Smith, Robert L., Smith, Thomas M. Elements of Ecology 4th Edition. Benjamin/Cummings Science Publishing. 1998

“Status Report Columbia River Fish Runs and Fisheries, 1938-1997.” Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. June 1998.

Winther, Oscar Osburn. 1948. The Great Northwest: A History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/archive/idx_map.htm

http://www.nps.gov/focl/

Fort Clatsop National Memorial

http://www.lewisandclarkeducationcenter.com

Lewis and Clark Education center

http://www.cpcbsa.org/districts/districts/ftclatsop/

Fort Clatsop District

http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/native/idx_cla.html

Clatsop Indians

http://www.nps.gov/focl/agee.htm

Forest landscape Fort Clatsop

http://www.sierraclub.org/ecoregions/pacnw.asp

Environment, Pacific Northwest

http://ens.lycos.com/ens/jun2001/2001L-06-01-02.html

Logging and Salmon

http://www.inforain.org/mapsatwork/oregonestuary/

Columbia River Estuary

http://www.columbiaestuary.org/channel/NWPPC.htm

Columbia River Channel deepening project

http://www.csc.noaa.gov/crs/lca/pdf/or_cr89-93_CR.pdf

Environmental changes on Columbia R ’89-’93

http://www.ocs.orst.edu/pub_ftp/climate_data/mme/mme0328.html

Climate data