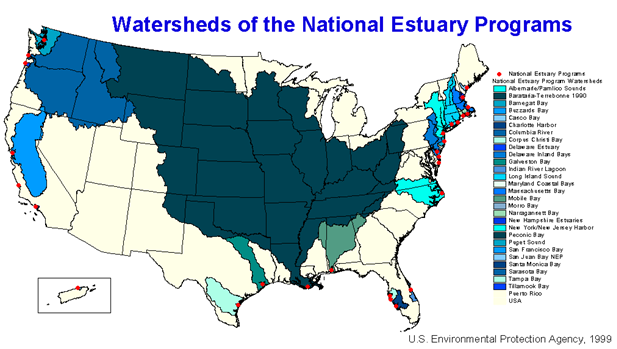

Figure 1. National Estuary Program Watersheds

Geographic Summary

False River

Louisiana

Summary information for the False River site is a compilation of existing sources and selected documents, Internet accessible data, which are referenced by section. Sources include, but are not limited to, college course web sites, BTNEP web site facts and commentaries, US Geologic Survey data, state and federal census data. The Geographic Summary is intended to provide a brief synopsis concentrating on the False River area and floodplain and related features. It is not meant to be an in-depth treatise on the geography and background of the area.

1. The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program . . ... 2.2

2. False River Geographic Summary . ...... 2.6

3. River Channel Morphology . ..... 2.7

Meandering Channels . ........... 2.7

Floodplains and Levees ....... 2.8

4. Flood Protection System .................................................................. 2.9

5. River Control and Maintenance ....................................................... 2.11

Ole River Control Structure . .......... 2.11

Morganza Spillway . ....................... 2.11

The Levee System . ........................ 2.13

6. Agriculture . ........................................ 2.13

Current Crops . .......... 2.13

Historical Crops .. .......... 2.14

7. Timeline of Ecosystem Alterations of the Mississippi River .... 2.16

8. Timeline of Ecosystem Restorations of the Mississippi River . .... 2.24

What is an estuary? An estuary is a place where freshwater meets with saltwater or where the river meets the sea. The Louisiana coast is an estuary but there is a special segment of the coast that is cherished as a national estuary; it is called the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary. This estuary has a serious problem; it is the fastest disappearing landmass on the face of Earth.

This Wetland Education Through Maps and Aerial Photography WETMAAP- is designed to help students learn about the northern area of the Barataria Terrebonne-National Estuary.

The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program is one of 28 congressionally mandated programs that recognize the national significance of this unique ecosystem. Under the guidance of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, this community based program, initiated in 1996, is designed to improve the health of the water, habitats, and living resources of this region.

The watershed of the Barataria-Terrebonne estuary is huge. It drains nearly two thirds of the central United States and is shown here in dark green (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. National Estuary Program Watersheds

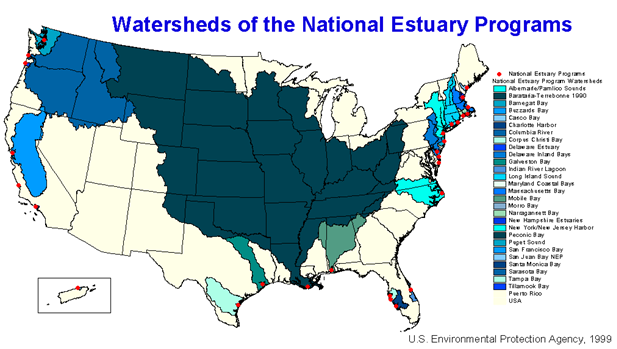

The Barataria-Terrebonne estuary is located in southeast Louisiana and includes all of the land and water between the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers. The system consists of two estuarine basins separated by Bayou Lafourche. The Terrebonne estuary lies to the west and the Barataria estuary to the east of this ancient course of the Mississippi River (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Location of the Barataria-Terrebonne Estuary in Louisiana

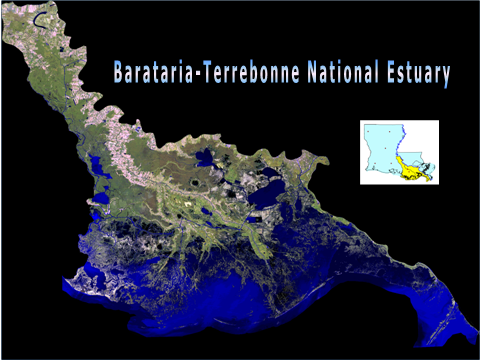

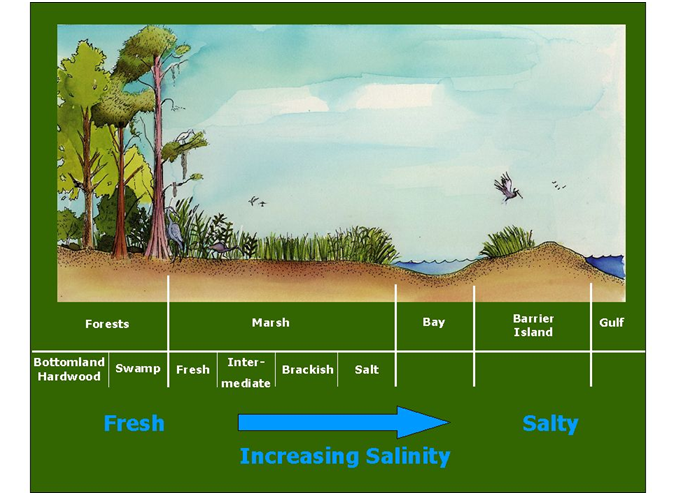

Barataria-Terrebonne contains some of the most diverse and fertile habitats in the world; this wedge shaped area between the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers contains landforms including levees, forests, swamps, marshes, islands, bays, and bayous (Fig. 3). The estuary is home to over 600,000 people. It provides food and shelter for millions of migrating birds including ducks, geese, songbirds and raptors. It is known for its abundant commercial harvest of over 600 million pounds of fish and shellfish each year. Wonderful resource animals such as the alligator, otter, deer and turkey have provided local residents with needed provisions throughout history.

Figure 3. Habitats of the estuary as related to salinity.

The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program was created to help solve environmental and conservation problems such as hydrologic modification, sediment reduction, habitat loss, eutrophication, pathogen contamination and toxics. The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program works with individuals, organizations, government entities, educators, legislators and a host of other groups to help protect, preserve, and conserve this unique ecosystem. This curriculum is designed to teach students about some of these issues as they are related to the northern area of the estuary.

This Wetland Education Through Map and Aerial Photography (WETMAAP) lesson series provided for the False River area of the estuary is a piece that can be used independently or with the other Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program (BTNEP) WETMAPP materials such as those created for Cocodrie and Golden Meadow, LA.

It is the hope of the BTNEP Education Action Plan team that this exceptional work will provide teachers and students with a exceptional opportunity to better understand the northern most area of the Barataria-Terrebonne Estuary.

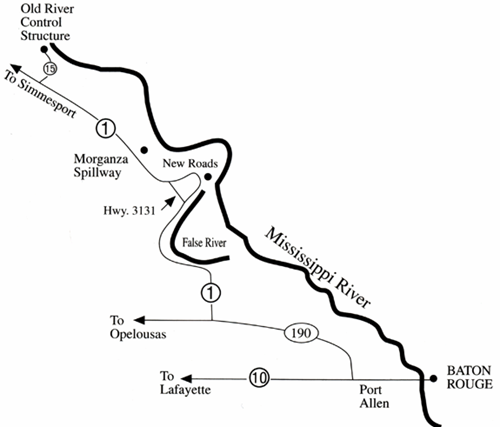

False River

False River is located 30 miles northwest of Baton Rouge on Highway 190 and Highway 1 ( Fig. 4). False River is a 22-mile long oxbow lake formed between 1713 and 1722 when the Mississippi River changed its course. The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers built the Morganza Spillway and The Old River Control Structure to maintain the current course of the Mississippi River and to control flooding of the area.

Figure 4. Location of the Old River Control Structure and Morganza Spillway.

Source: http://www.btnep.org/minis/fieldtrip/trip20.htm

River Channel Morphology

Moving or flowing water is one of the powerful forces that shape the physical landscape. Fluvial processes scour, carve, deposit, and modify landform features. Rivers are active agents of erosion, transportation, and deposition of materials. River erosion is a process where material (e.g., rock, soil), is detached and removed. Transportation is the movement of depositional materials (e.g., rock, soil) from their original position to a new location. Deposition is the setting down of materials (e.g., rock, soil) in a new location. This process causes changes in river channels.

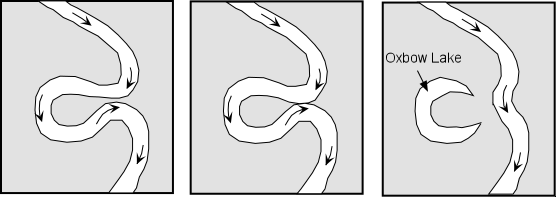

A floodplain is a flat, low area characterized by periodic inundation by overflow from a stream or river and has a meandering river, meander scars, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. The Mississippi River is a meandering river that has smooth curves that bends and twists in a continuous pattern. A loop or bend of the river can be cut off from the main channel when deposition occurs on the inside of the bend and erosion occurs on the outside of the bend (literally pinching the river at the neck of the bend) and forms an ox bow lake.

Meandering Channels

From: Prof. Stephen A. Nelson, Tulane University,

Physical Geography web site:

http://www.tulane.edu/~sanelson/geol111/streams.htm

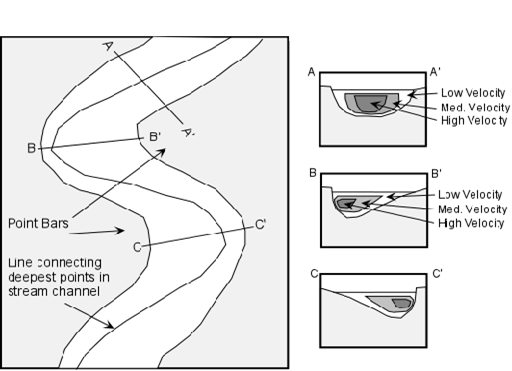

Because of the velocity structure of a stream, and especially in streams flowing over low gradients with easily eroded banks, straight channels will eventually erode into meandering channels. Erosion will take place on the outer parts of the meander bends where the velocity of the stream is highest. Sediment deposition will occur along the inner meander bends where the velocity is low. Such deposition of sediment results in exposed bars, called point bars. Because meandering streams are continually eroding on the outer meander bends and depositing sediment along the inner meander bends, meandering stream channels tend to migrate back and forth across their flood plain.

If erosion on the outside meander bends continues to take place, eventually a meander bend can become cut off from the rest of the stream. When this occurs, the cut-off meander bend, because it is still a depression, will collect water and form a type of lake called an oxbow lake.

Floodplains and Levees

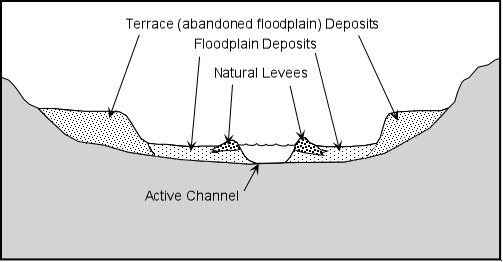

If water flow or stream discharge is suddenly increased, as it might be during a flood, the stream will overtop its banks and flow onto the floodplain where the velocity will then suddenly decrease. This results in deposition of such features as levees and floodplains.

As a stream overtops its banks during a flood, the velocity of the flood will first be high, but will suddenly decrease as the water flows out over the gentle gradient of the floodplain. Because of the sudden decrease in velocity, the coarser grained suspended sediment will be deposited along the riverbank, eventually building up a natural levee. Natural levees provide some protection from flooding because with each flood the levee is built higher and therefore discharge must be higher for the next flood to occur.

Terraces are exposed former floodplain deposits that result when the stream begins down cutting into its flood plain (this is usually caused by regional uplift or by lowering the regional base level, such as a drop in sea level).

Flood Protection System

Source: Loyola University of New Orleans Center for Environmental Communications

(

http://www.loyno.edu/lucec)

For ages, the Mississippi River followed a similar pattern year-after-year. As the water began to rise in the spring, the river would leave the depths of its channel and fill the batture of the natural levee. All backwater areas would slowly fill. When non-native Americans came on the scene, they began to build levees that protected them from floods during most years. Occasionally, higher water would result in flooding, so the local folks would build the levees higher.

After the great floods of 1927, the public mandated that Congress solve the flooding problems of the lower Mississippi River basin. They did so by constructing a levee and "relief valve" (spillways and related structures) system.

A natural sequence of events that occur each spring that protect the lower river basin from flooding:

- Water begins to pool into a large back swamp area in Avoyelles and Concordia parishes. This area is a vital part of the system because it holds so much water and gradually drains as the waters recede through the summer months.

- As the back swamp fills, water rises in the river channel and covers the batture. In the Atchafalaya, this occurs between the internal levees that are along the margins of the river above the latitude of Baton Rouge. The water spreads to cover the entire floodway between the guide levees that extend southward all the way to the Atchafalaya Bay.

- The flow rates of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya increase, but remain in the 70%/30% ratio.

If the predictive model used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers indicates that these three steps will not prevent flooding, human operated structures are used:

- Bonnet Carrι Flood Control Structure: When the water reaches a critical stage (it was originally designed to keep the Carrollton Gauge, located at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers headquarters at the river on River Road, New Orleans, Louisiana below the 20 ft mark - which kept the river 5 ft below the top of the levee), this flood control structure is opened to allow up to 250,000 cfs (cubic feet per second) of water to flow into Lake Pontchartrain through the Bonnet Carrι Spillway. It has been operated eight times (1937, 1945, 1950, 1973, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1997).

- Morganza Control Structure: After the Bonnet Carrι Flood Control Structure is opened, and if the river continues to rise to the next critical stage, this structure is opened. It shunts up to 600,000 cfs into the Atchafalaya River through the Morganza Spillway. Since this is a very rare occurrence (it has only been opened once, in 1973), the rich soils of the spillway are allowed to be used for farming, especially for cattle and soybeans. If it has to be used, the lessors are notified and, if they cannot remove their animals and crops, they lose them when the waters are released through the structures.

- Fuse Plug Levee: If all the above procedures are not enough to handle the flood stage of the river, the last resort is the Fuse Plug Levee. This is an east-west running levee located between the west guide levee and the west internal levee along the Atchafalaya. To its north lies the great back swamp area; to its south lies the West Atchafalaya Floodway. The Fuse Plug Levee is lower than the adjacent west guide west internal levees. If the water in the back swamp is not contained by all the above steps, then water begins to flow over the fuse plug levee rather than over adjacent levees where it would flood human habitations. Once water begins to flow over the top of the Fuse Plug Levee, it quickly tears it down until it carries a maximum of 250,000 cfs. This is designed to work on its own, but if extremely critical, it can be dynamited. To date, the Fuse Plug Levee has never been needed.

River Control and Maintenance

Sources:

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District

(http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil)

Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary

(http://www.btnep.org)

Louisiana State University Department of Geology and Geophysics

(http://www.geol.lsu.edu)

Tulane University

(http://tulane.edu/)

Old River Control Structure

In order to preserve the present course of the river, a project was authorized by PL 780, 83rd Congress, approved in September 1954 (a modification of the Flood Control Act of May 1928), to maintain the balance of flows from the Mississippi River into the Atchafalaya River and Basin by control structures on the right bank of the Mississippi River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for operation and maintenance of all project features except the main line Mississippi River levee and road. Principal features include a low sill control structure with inflow and outflow channels, an overbank control structure, an auxiliary control structure, a navigation lock and channels, levees, closure of Old River, and bank stabilization as required.

Morganza Spillway

The Morganza Spillway (Fig 4.) is located in the northernmost tip of the Barataria-Terrebonne Estuary. Just to the north of the spillway, is the Old River Control Complex, built between 1957 and 1986. These two Mississippi River control structures impact the estuary by controlling the inflow of freshwater from the Mississippi River. The structures prevent the capture of the Mississippi River by the Atchafalaya River.

The Morganza Floodway is capable of introducing excess floodwaters from the Mississippi River to the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway at a rate of 600,000 cubic feet per second (4.5 million gallons per second). The structure was constructed in 1954 and was operated for the first and only time when partial opening was made during the 1973 flood to lower Mississippi River stages and relieve pressure on the Old River Low Sill Control Structure.

The floodway consists of a combined gated control structure, high level highway and railroad crossings over the floodway, drainage alterations, and improvements. Comprehensive easements for full use of the lands within the floodway have been acquired between the guide levees. Habitation within the floodway is not permitted, but use of the land for farming, removal of timber and minerals, and other purposes not in conflict with flood control are permitted with prior approval.

Morganza Combined Control Structure. The structure consists of about 19,340 linear feet of levee and a reinforced concrete structure consisting of 125 gated openings, each 28 feet 3 inches wide, separated by three (3) foot wide piers. Each opening is equipped with a steel vertical lift gate operated by a gantry crane. Bridges for the gantry crane, Louisiana Highway 1, and the joint track for the Kansas City Southern and Texas and Pacific Railways are supported by piers between the earth embankments flanking the control structure. The structure was completed in 1954 at a cost of $20,680,000.

Morganza Floodway Levees. The levees consist of the upper and lower guide levees which, with the East Atchafalaya River levee, form a floodway averaging about five (5) miles wide.. The upper guide levee extends about nine (9) miles southwesterly from the combined control structure to the East Atchafalaya River levee, about two (2) miles upstream from Melville. This levee protects more than 100 square miles of productive farmlands in upper Pointe Coupee Parish from overflow during floodway operations. The lower guide levee extends about 19.4 miles in a southerly direction from the control structure to join the East Atchafalaya Basin protection levee at the latitude of Krotz Springs.

Pointe Coupee Drainage Structure and Bayou Latenache. A drainage system for the Upper Pointe Coupee Parish area, which is protected by the upper guide levee, was provided with a drainage structure at the intersection of the levee and Bayou Latenache. The bayou was enlarged from the drainage structure to U.S. Highway 190. The structure, located about 0.5 mile east of the Atchafalaya River, consists of a reinforced concrete structure supported on untreated timber piles and contains two motor operated steel lift gates, each 10.5 feet wide and 15.0 feet high. This feature was completed in 1942 at a cost of $310,000. Operation and maintenance are the responsibility of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Inundation rights have been acquired on 12,800 acres of land above the drainage structure for storage of runoff during the closure of the gates, for operation of the Morganza Floodway. Additional drainage work has been authorized for the upper Pointe Coupee area. Initially, improvements included the enlargement of Bayou Latenache, a U. S. Army Corps of Engineers responsibility, and construction of an interior drainage system of major laterals and on farm drains by others.

Pointe Coupee Pumping Station was designed and constructed as a result of initial area drainage studies and restudies conducted prior to and following the 1973 flood. This pumping station was constructed in lieu of enlarging Bayou Latenache, as initially planned. Construction began in 1980 and was completed in October 1983; the station was first operated for removal of floodwater from the upper Pointe Coupee loop area in December 1983. The station floodwater pumping system consists of three diesel engine driven, 500 cubic feet per second pumps that are progressively activated as needed to limit floodwater accumulations above the pumping plant to 26.0 feet NGVD, with progressive deactivation as levels are drawn down. The station structure is reinforced concrete set on driven steel piling. The station discharges into the Atchafalaya River through three 84 inch diameter pipes over the East Atchafalaya River levee, about 0.2 mile north northwest of the Pointe Coupee Drainage Structure. This $15 million station is expected to minimize the duration of flooding in this leveed loop area and ensure larger crop acreage availability.

The Levee System

The flood of 1927 effectively dispelled the notion that "levees only" were the only method of flood control. Crevasses occurred everywhere, each time with disastrous effects. Examples are at Mounds Landing, Mississippi, and the artificial crevassing at Caernarvon below New Orleans. The rising torrent of the river in 1927 was exacerbated by the fact that, over the last one hundred years, the levees simply were built higher and higher.

Rivers naturally want to overflow their banks. It is part of their physical dynamic. Therefore, by building levees higher and higher, the natural force of the water is bottled up. This force, when broken open, is devastating. Yet, prior to 1927, those in power refused to see the need for outlet channels. Yet, as a result of the 1927 flood, outflows have been the focus of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers flood control plans for the last seventy years, with good results.

With the need for increased farmland and residential areas, levees provide an invaluable function. Essentially, the Mississippi River levees and the levees that are found on its tributaries serve the function of confining the river's flow to a certain channel during normal river operation. It is when high water comes that pressure is taken off of the levee system by diverting water through outlets such as the Old River Control Structure, the Bonnet Carre' Spillway, and the Morganza Floodway. This relieving of pressure is what has held the levee system of the lower Mississippi River Valley in check for much of the last seventy years.

Agriculture

A focal point for the False River site is agriculture including the Alma Plantation Sugar Mill, which produces raw sugar and black strap molasses. The plantation home was built in 1789 by noted philanthropist Julien Poydras and now owned and operated by the Stewart Family.

Current Crops

The dominant agricultural crops grown within the New Roads and False River areas and of Pointe Coupee Parish include corn, cotton, rice, sorghum, soybean, sugarcane, wheat (see Statistics, section 4.8 of the Educators Supplement for detailed production yields.) Yields for each of these crops have steadily increase increased since the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, there has been fluctuation in productions with marked decreases in yields of cotton (1980-1990), sorghum (1993), and sugarcane (1985-1990).

Historical Crops

The original impetus for settling the False River area came from two facts of geography: the cut-point (or "pointe coupee" in French) where a trip up the Mississippi River could be considerably shortened, and the agricultural possibilities of the region itself. The crops that first drew settlers to the area were tobacco, sugar cane, pecans, and indigo.

Tobacco was a major agricultural product and that part of Pointe Coupee Parish adjacent to modern-day False River was a nexus of the Louisiana tobacco trade, with government regulators and merchants congregating here to service both the locals and tobacco farmers upstream.

Research shows that sugar was not grown in Louisiana under French rule. General consensus of the time was that Louisiana was at too high of a latitude to successfully grow sugar. Jesuits first brought the crop to Louisiana in 1751, but it was not exploited commercially until 1795, when French Louisianan Etienne de Bore sold his locally-grown sugar for $12,000. After control of the colony passed into American hands, the first grower on record in Pointe Coupee Parish was Judge Ludling.

The first sugar mill in Pointe Coupee was established in 1814, and the War of 1812 disrupted the first production. Nonetheless, sugar seems to have caught on, as production continues to this day.

Pecan production also is tightly linked to the history of the area. Unlike sugarcane or tobacco, the crop was native to the area; first sighting by Europeans was in nearby Texas, by Cabeza da Vaca while shipwrecked on Galveston Island in the 1540s. French explorers mentioned it in the 1700s, discovering it in Louisiana Territory. It quickly became a delicacy, and Le Page du Pratz (2006, 94) mentioned its use in "the pralaine... sugar cakes or candies filled with ... pecan kernels ... and one of the delicacies of New Orleans." French colonists began exporting pecans from Louisiana by 1802. The first recorded shipment of any kind from Louisiana was a box of "paccan nuts" sent to Thomas Jefferson's estate at Monticello by Daniel Clark, a resident of New Orleans, in 1779. Louisiana was also the first state to graft pecan trees-in 1847-and the first to grow and sell pecans commercially.

Indigo was one of the original cash crops of the New World. Native to India, Africa, Australia and the Americas, indigo supplanted woad as the principal blue dye for Europeans by the 1600s. However, the indigo monopoly held by India drove up prices for the Europeans, and Europe countered by cultivating it in its colonies. The crop was introduced to French Louisiana by 1719, as well as African slaves with which to plant, harvest, and process the crop. The Europeans and local natives had relatively little expertise with indigo, so expertise of slaves from the Senegal region was crucial to the industry. However, the crop's value fell sharply after the American Revolution, and was largely phased out of production in favor of cotton and sugar cane (The Devils Blue Dye: http://www.slaveryinamerica.org).

Cotton got its start as a cash crop in America in South Carolina. Cut off from Indian cotton imports via Britain, the American rebels urged local cotton production in order to clothe the Continental Army. By the end of the Revolutionary War, cotton was a major export crop and was spreading quickly across the South. It reached Louisiana by the early 1800s, after the invention of the cotton gin threw profit margins wide open and put it firmly in the province of slave-owning plantations. The Civil War disturbed and reformed the industry, which now was ran on the backs of freed black sharecroppers. After World War II, mechanization hit the industry and increased yields while lowering labor input, and cotton remains a valuable product to this day.

Agricultural Sources:

Debow's Southern and Western Review. July 1851, p. 631

du Pratz, Le Page. 2006 The History of Louisiana. Bibliobazaar, LLC. p. 94.

Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (http://www.codofil.org)

LSA Agricultural Center (http://www.lsuagcenter.com)

Rosalie Pecans (http://www.rosaliepecans.com)

Slavery In America (http://www.slaveryinamerica.org)

Tucker Pecan Company (http://www.tuckerpecan.com)

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service (http://nass.usda.gov)

Timeline of Ecosystem Alterations of the Mississippi River

The timeline information is extracted from the Northeast Midwest Institute

(http://www.nemw.org), which is a Washington-based, private, non-profit,

and non-partisan research organization Northeast and Midwest states.

Portions of the information have been modified.

General Survey Act of 1824:

Authorized the President to employ civil engineers and officers of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to make surveys, plans, and estimates for roads and canals of national importance for the transportation of public mail.

Roads and Canals Act of 1824:

Appropriated $75,000 to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to improve navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers by removing sandbars, snags, and other obstacles.

Rivers and Harbors Act of 1826:

Authorized the President to have river surveys undertaken to clean out and deepen selected waterways and to make various other river and harbor improvements.

Mississippi River flood, 1828:

The Mississippi River flood of 1828 caused widespread damage to the region; generally believed to be the greatest flood of the nineteenth century.

Swamp Land Acts of 1849, 1850 and 1860:

The Swamp Land Act of 1849 granted to Louisiana all swamp and overflow lands then unfit for cultivation, to help in controlling floods in the Mississippi River Valley. Collectively, the Swamp Land Acts of 1849, 1850, and 1860 granted more than 9 million acres of swamp to Louisiana and nearly 65 million acres of wetlands in 15 states from the federal government to state governments to expedite drainage.

Charles Ellet Report, 1852:

Charles Ellet, a civil engineer working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, completed a topographical and hydrographical survey of the delta of the Mississippi River. His report to Congress advocated greater federal responsibility for the control of floods in the lower Mississippi River and favored a comprehensive plan for controlling floods that, in addition to levees, included the construction of reservoirs and diversion channels.

Publication of Mississippi River Report, 1861:

Engineers Humphreys and Abbot released their report on the physics and hydraulics of the Mississippi River; completed after more than ten years of exhaustive research. The report represented the most thorough analyses of the Mississippi River to date, both in terms of data gathered and conclusions rendered. It also influenced the development of flood control policy on the river system well into the twentieth century.

Flood and Warren Commission Report, 1874:

A great flood in 1874 exploited the still weakened levee system of the Mississippi River and wrecked havoc on the lower valley. The federal government redirected its attention to the flood problems of the delta. The U.S. Congress approved an act creating a commission of engineers "to investigate and report a permanent plan for the reclamation of the alluvial basin of the Mississippi River subject to inundation." To that end, President Grant appointed General G. K. Warren as commission chairman and appropriates $25,000 for the study. After considerable analysis of the flood problem in the delta, the Warren Commission criticized the efforts and methods of local flood control and emphasizes the need for greater federal commitment to control the Mississippi River. The report's solid recommendation for greater federal commitment stimulated the growth of favorable public sentiment and encouraged flood control advocates in Congress.

Creation of House Standing Committee on Mississippi Levees, 1875:

House Speaker Michael C. Kerr of Indiana authorized the creation of a House Standing Committee on Mississippi Levees. Beginning with its inception in December 1875, the Committee became the voice for flood control interests in Congress and remained so for more than thirty-five years.

Mississippi River Commission Act of 1879:

Representing the first federal attempt to develop a coordinated plan for the development of the Mississippi River, Congress established the Mississippi River Commission; a seven-member advisory board made up of three U.S. Army Corps of Engineers representatives, one Coast and Geodetic Survey representative, and three civilians (at least two of whom must be engineers). Congress tasked the Commission with developing and overseeing the implementation of plans to "improve and give safety and ease to navigation" and to "prevent destructive floods" on the Mississippi River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was charged with conducting the work, and also with supplying necessary plants and equipment.

Flood Control, 1880s:

Construction of flood control structures throughout the Upper Mississippi River System by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. By constraining and redirecting the river channel and cutting it off from its floodplain, the flood control measures greatly altered the hydrology of the entire Mississippi River system as well as the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems it supported.

Congressional Appropriation Bill, 1881:

Included a provider restricting the Mississippi River Commission's authority to construct levees for the purpose of flood control.

Congressional Appropriation Bill, 1882:

Authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to undertake levee construction for the purpose of improving navigation, but not for flood control.

Rivers and Harbors Appropriations Act, 1882

Combined appropriations for development of the nation's waterways with a reaffirmation of the policy of freedom from tolls and other user charges. The Act signaled Congress' intent to improve waterways to benefit the nation by promoting competition among transportation modes.

Dam construction, 1884 1912:

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of six dams on the Upper Mississippi River in Minnesota to stabilize water levels downstream. Construction was complete by 1912.

Mississippi River flood, 1890

The Mississippi River flood of 1890 proved that levees on the river system were inadequate and focused Congressional attention on river problems.

River and Harbor Act of 1890:

The River and Harbor Act of 1890 appropriated $3.5 million to the Mississippi River Commission in reaction to the severe Mississippi River flood of 1890. For the first time, the bill language did not include the standard provider against levee construction for the purpose of controlling floods. The landmark piece of legislation contributed to the rapid expansion of levee construction under the Mississippi River Commission.

Mississippi River Commission, 1896:

The Mississippi River Commission admitted that its attempts to improve navigability of the Mississippi River through bank revetment and contraction works, had generally failed. The temporary abandonment of these expensive river improvement efforts allowed the Commission to concentrate a greater percentages of its resources on the construction of levees.

Mississippi River flood, 1897:

The devastation caused by the Mississippi River flood of 1897 forced Congress to reassess the value and direction of its flood control program for the Lower Mississippi River.

Nelson Report, 1898:

The Nelson report advocated for the continuation of a levees-only policy for the Lower Mississippi River.

Mississippi River flood, 1898:

For the first time since the initiation of a continuous levee line along the Lower Mississippi River, the Mississippi River flood of 1898 was safely discharged to the Gulf of Mexico without a single break in the levees.

River and Harbor Act of 1894:

Authorized the Secretary of the Army to prescribe rules and regulations for the use, administration, and navigation of any or all canals and similar works of navigation owned, operated, or maintained by the United States.

River and Harbor Act of 1899:

Authorized approval for the construction of bridges, dams, and dikes across any navigable water of the United States. The Act also required that structures built under state authority require approval from the Chief of Engineers and the Secretary of the Army. The Act prohibited the placement of obstructions to navigation outside established federal lines and excavating from or depositing material in such waters unless a permit for the works had been authorized by the Secretary of the Army.

Levee building, wetlands draining, canal digging, 1900s:

Louisiana residents continued to fight the constraints imposed by the area's coastal ecosystem, building levees to guard against flooding, draining wetlands to expand usable land, digging canals to expand drainage and navigation networks, and providing access for transport of timber, oil, and gas.

Mississippi River flood, 1903:

The Mississippi River flood of 1903 breached the levees. According to the Mississippi River Commission, all crevasses in the line resulted from the "unfinished nature of the levees as regards both grade and section." The push for higher levees continued.

Interstate Inland Water League, 1905:

With the goal of forming a continuous system of 18,000 miles of navigable waters extending from the Great Lakes through the Mississippi Valley and along the Louisiana and Texas coastlines, a convention in Texas created the Interstate Inland Waterway League. The league eventually became known as the Gulf Intracoastal Canal Association.

River and Harbor Act of 1906:

Expanded the jurisdiction of the Mississippi River Commission by authorizing the construction of levees between the Head of Passes south of Venice and Cape Girardeau, Missouri; it extended the Commission's responsibilities for levees above Cairo, Illinois, to the head of the St. Francis Basin.

Rivers and Harbors Act of 1907:

Congress appropriated $89,292 in the Rivers and Harbors Act to connect the Bayou Teche at Franklin with the Mermentau River, the first Louisiana segment of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway.

Mississippi floods of 1912 and 1913:

The Mississippi Valley experienced successive record-breaking floods which precipitated a crisis in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reclamation program. The tremendous expense incurred as a result of the regular inundation of the Valley, combined with the cost of building, maintaining, and repairing the levee system, became counter-prohibitive. Out of self-preservation, landowners in the valley launched a massive propaganda campaign directed at obtaining greater federal commitment.

Townsend Report, 1913:

President Woodrow Wilson directed the Mississippi River Commission to submit a report on flood control Following the Mississippi River flood of 1913. The report considered six methods of flood control: reforestation, reservoirs, cut-offs, outlets, floodways, and levees. The Commission condemned the various alternatives to levees and advocated for a continuation of policy.

River and Harbor Act of 1913:

Expanded the Mississippi River Commission's jurisdiction to Rock Island, Illinois, with certain restrictions.

Ransdell-Humphreys Act of 1917:

The first federal flood control act committed the federal government to flood control for the Mississippi Valley. The Act also extended the Mississippi River Commission's jurisdiction to include water-courses connected with the Mississippi River to the extent necessary to exclude flood waters from the upper limits of any delta basins.

Flood Control Act of 1923:

Authorized $60 million for levee construction over a ten-year period for the purpose of completing the levee system along the Lower Mississippi River.

Inland Waterways Corporation, 1924:

Congress created the Inland Waterways Corporation to promote, encourage, and develop water transportation, service, and facilities in connection with the commerce of the United States, and to foster and preserve both rail and water transportation. To fulfill the water transportation provision, the Corporation operated barges under the name Federal Barge Lines on the Mississippi-Missouri and Warrior Rivers.

Levee system complete, 1926:

The Mississippi River Commission concluded in its annual report that the river's levee system "is now in a condition to prevent the destructive effects of floods."

River and Harbor Act of 1927:

Authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to undertake comprehensive surveys and formulate general plans for the most effective improvement of navigable streams and their tributaries, and the prosecution of these improvements in combination with the development of potential water power, the control of floods, and the need for irrigation. The surveys, called "308 reports," established the first comprehensive river-basin development plans for the nation and provide authority to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for surveying and planning navigation systems for inland waters.

Great Mississippi Flood of 1927:

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 devastated the Mississippi River region. The Mississippi River Commission's prized levee system (the culmination of almost fifty years of work) proved unequal to the task. The high water caused 17 breaks in the main levee line and 209 crevasses on the tributaries of the Mississippi. The flood waters overflowed an estimated 11,000,000 acres from Cairo, Illinois, to Natchez, Mississippi, on the west bank and from the mouth of the Arkansas River to Vicksburg, Mississippi, on the east bank. The Lower Mississippi Valley, including parts of seven states, remained flooded for five months. Total property loss and damage was estimated at between $200 and $400 million, exceeding the aggregate losses of all previous Mississippi floods.

Flood Control Act of 1928:

In response to 1927 flood disaster, Congress overhauled the flood control plan for the Lower Mississippi River. The Flood Control Act of 1928 authorized the Mississippi River Commission to implement Chief of Engineers, Major General Edgar Jadwin's plan for controlling floods on the Lower Mississippi River, including the abandonment of a levees-only policy and the adoption of a comprehensive flood control plan using floodways and spillways, including through the Atchafalaya Basin, as well as levees. The plan provided for enlarging and strengthening the levees from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to the Gulf of Mexico, with the objective of safely discharging up to 1,500,000 cubic feet/second of water within the main channel.

Mississippi River Commission cut-off policy, 1932:

The Mississippi River Commission initiated a series of cutoffs in the middle reaches of the Mississippi River based on studies by the newly created Waterways Experiment Station Within nine years, 16 such cutoffs shortened the distance from Memphis, Tennessee, to Vicksburg, Mississippi, by 170 miles and reduced flood heights along the main channel considerably. The successful development of these cutoffs marked a new phase in the evolution of flood-control engineering.

Congressional Resolution, 1932:

The resolution requested an examination and review of the status and condition of works, then in progress, as authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1928, with a view to determining if changes or modifications should be made in relation to the project and its final execution.

Overton-Dear Act of 1934:

Resolved the bitter controversy from conflicting interpretations of the Flood Control Act of 1928. In the Act, the government abandoned its efforts to compel owners of property along the tributaries of the Lower Mississippi River to donate levee rights-of-way at no cost to the Government.

Review of flood works report, 1935:

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers submitted a report to Congress reviewing the status and condition of works then in progress as authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1928 and in accordance with the Congressional resolution of 1932. The report concluded that the New Madrid Floodway levees at Cairo, Illinois, were nearly complete; the Bonnet Carre Spillway at New Orleans, Louisiana, was essentially complete; and neither of the larger floodways (Morganza and Boeuf) was yet under construction.

Ohio-Mississippi River flood, 1937:

The flood forced operation of the New Madrid floodway at Cairo, Illinois and the Bonnet Carre Spillway near New Orleans, Louisiana. The cutoffs initiated in 1932 along the Mississippi below the mouth of the Arkansas River accelerated discharges and lowered flood heights by as much as five feet.

Outbreak of World War II, 1940:

Promoted the recovery of the national economy, and substantially increased Mississippi River commerce. Unimpeded navigation also became essential for military operations; almost 4,000 Army and Navy craft moved from inland shipyards down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico.

Flood Control Act of 1941:,

Congress removed plans for construction of the Eudora Floodway from the Mississippi River Commission's series of projects in favor of higher levees at the of the Arkansas delegation. The project included a combination of levees, drainage structures, and pumps.

Congressional resolution, 1943:

The House Flood Control Committee and the Senate Committee on Commerce passed a resolution calling on the U.S. Army Corps' Chief of Engineers and the Mississippi River Commission to submit a report on the feasibility of amending the navigation provisions of the Flood Control Act of 1928, with specific reference to increasing channel depths from 9 to 12-feet from Cairo, Illinois, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Mississippi River flood, 1943:

The Mississippi River reached its second highest level in recorded history. Cape Girardeau, Illinois, recorded a level of 42.3 feet.

Mississippi River Commission report, 1944:

The Mississippi River Commission released (at the request of Congress) its report on the feasibility of increasing channel depths below Cairo, Illinois. After thorough analysis, the Commission concluded that stabilization efforts already underway, together with additional dredging, might be enough to provide a 12-foot deep channel below Cairo, Illinois.

Flood Control Act of 1944:

The Flood Control Act of 1944 authorized approximately 150 additional projects throughout the nation at a cost of $750 million, including approval for a 12-foot channel in the Mississippi River between Cairo, Illinois, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as well as a $200 million stabilization program. The Act also required all subsequent navigation and flood control projects be subject to the approval of the affected states. The Act articulated a new policy for the development of recreation facilities at reservoirs, stipulating that public reservoirs be open for public use without charge for boating, swimming, bathing, fishing, and other recreational purposes. This new responsibility represented an important step toward multi-purpose development of the nation's water resources.

Atchafalaya Basin study, 1950:

A major U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study determined that, without interference of some kind, Louisiana's Atchafalaya Basin would capture the Mississippi River by 1975. To prevent this, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers urged Congress to authorize the construction of a controlled connection along the Old River in order to regulate the volume of water allowed into the Atchafalaya Basin.

Levee system construction, 1950s-1970s:

Construction of an extensive levee system along the Mississippi River, with the goal of maintaining navigation and reducing the flooding of adjacent homes and businesses, began in the 1950s. The system prevented Louisiana's coastal wetlands from receiving their regular nourishment of riverine water, nutrients, and sediment -- a diet crucial to wetland survival. These regional impacts were exacerbated by other hydrologic alterations that modified the movement of freshwater suspended sediment, and saltwater through the system. Canals dredged for navigation, or in support of mineral extraction, allowed saltwater to penetrate into previously fresh marshes. In time, efforts to open and maintain navigation channels to the Gulf disrupted the Chenier Plain's stable wetland system and dredged ship channels allowed salt water into previously isolated freshwater marshes, particularly during hurricanes.

Mississippi River Commission report, 1954:

The Mississippi River Commission reported that its flood control efforts had progressed to the point that most of the inhabitants of the Mississippi Valley were now safe from a 1927-caliber flood. Seventy-five percent of the bank revetment was completed, and only 250 miles of main-line levees remained unfinished.

Hurricanes, 1960s 2002:

In 1965, the eye of Hurricane Betsy passed 50 miles west of New Orleans. Tidal water surged in Plaquemines, St. Bernard, and Orleans Parishes, causing $2 billion in damages and 81 deaths. Following Hurricane Betsy, work began on a billion-dollar hurricane protection system around the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain. Completed in 2002, the system in theory would be be able to shelter the city from a Category 3 hurricane storm surge. But in reality, whether or not a surge overtops the levees depended on the storms. [Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, 1995, proved otherwise.]

Flood Control Act of 1960:

Authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to compile and disseminate information on floods and flood damage, to identify areas subject to overflow, and to present general criteria for guidance in the use of flood plain areas.

River and Harbor and Flood Control Act of 1965

The River and Harbor and Flood Control Act of 1965 authorized 150 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers projects or project modifications at an estimated cost of $2 billion, including a long-range master plan for stabilizing the Mississippi River between Cairo, Illinois, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to facilitate the establishment of a 12-foot channel depth.

Mississippi River flood, 1973:

Caused widespread damage, resulting in 23 deaths, and a record 62 days-out-of-bank. Total cost of the flood was estimated at $183 million.

Mississippi Delta Flood Control Projects, 2004

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers moved forward with a controversial plan for two flood-control projects in the Mississippi Delta that would drain tens of thousands of acres of flood-prone wetlands and dredge more than 100 miles of river bottom in an effort to boost agricultural production, remove contaminated soil, and protect about 1,500 homes from flooding.

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita hits Gulf Coast, 2005

The Gulf Coast of the United States was hit by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, destroying much property and rendering much of New Orleans uninhabitable. The 17th Street cannel levee was breeched. Government efforts to restore the area are still underway. Efforts to prevent such widespread damage in the future focus on restoring wetlands in barrier regions, strengthening levees, and documenting the changes made by the storm.

Timeline of Ecosystem Restorations of the Mississippi River

The timeline information is extracted from the Northeast Midwest Institute

(http://www.nemw.org), which is a Washington-based, private, non-profit,

and non-partisan research organization Northeast and Midwest states.

Portions of the information have been modified.

Rivers and Harbor Act of 1899:

Gave authority to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to regulate the dumping of pollutants in navigable streams.

Inland Waterways Commission, 1907:

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed the Inland Waterways Commission to develop a national policy for river regulation and to make recommendations for the improvement of the national system of waterways. A report released in 1908 by the Commission advocated for the creation of a permanent commission to coordinate the various federal agencies responsible for regulating the nation's water resources including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Soils, the Forest Service, the Bureau of Corporations, and the Reclamation Service, and to consider, among other things, all matters of irrigation, swamp and overflow land reclamation, and flood control. The Mississippi River Commission strongly opposed creation of a permanent commission and, together with its allies in Congress, delayed the establishment of a permanent Inland Waterways Commission for a full decade.

Creation of the Mississippi River Parkway Commission, 1938:

Established the Mississippi River Parkway Commission, a multi-state organization comprised of members from each of the ten states that border the Mississippi River, to facilitate development of the Great River Road Parkway.

Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1958:

Authorized that fish and wildlife conservation receive consideration equal to that of other project purposes and be coordinated with other features of water resource development.

Forest Conservation Act of 1960:

Authorizing the U.S. Corps of Engineers to provide for the protection and development of forest and other vegetative cover, and the establishment and maintenance of other conservation measures for all U.S. Army Corps of Engineers projects.

Water Resources Planning Act of 1965:

Established a Water Resources Council composed of Cabinet representatives to maintain a continuing assessment of the adequacy of water supplies in each region of the United States, and established principles and standards for federal participants in the preparation of river basin plans and in evaluating federal water projects. The Act also established river basin commissions, and stipulated their duties and authorities. The Act established a grant program to assist states in participating in the development of related comprehensive water and land use plans.

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969:

Authorized preparation of the environmental impact statement as an integral element of the U.S. Corps of Engineers' pre-authorization process on all projects and permit-granting activities. The Act instructed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to take into consideration the sociological, cultural, biological, demographic, and economic effects and consult with local, state, and federal agencies, as well as concerned citizen groups, in the process of producing environmental impact statements.

Environmental Quality Improvement Act of 1970:

Provided for the submission and promulgation of guidelines for considering possible adverse economic, social, and environmental effects of proposed projects, and expressed Congress' intent that federally-financed water resource projects incorporate the objectives of economic development; the quality of the total environment, including its protection and improvement; the well-being of the people; and the national economic development.

Act 35 of 1971 of the Louisiana State legislature, 1971:

Louisiana's Legislature established the Louisiana Advisory Commission on Coastal and Marine Resources to determine the needs and problems of coastal and marine resources. The Commission published three major reports: "Louisiana Government and the Coastal Zone - 1972," "Wetlands '73: Toward Coastal Zone Management in Louisiana," and "Louisiana Wetland Prospectus."

Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972:

Complementary to the Environmental Quality Improvement Act of 1970, the Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 created guidelines affecting standards applied by the U.S. Corps of Engineers in its environmental impact statements, as well as reinforced the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers' perceptions of changing national priorities.

Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1980:

Provided funds to states to conduct inventories and conservation plans for conservation of non-game wildlife. The Act also encouraged federal departments and agencies to use their statutory and administrative authority to conserve and promote conservation.

Act 41 of the Second Extraordinary Session of 1981 of the Louisiana Legislature, 1981:

Created a one-time $35 million fund for conducting applied research and physical projects to address coastal restoration in Louisiana. The Act also resulted in the formation of the Coastal Protection Task Force which in a report to Governor Treen in 1982 recommended five projects and a study be carried out focusing on barrier islands and shorelines.

Barataria and Terrebonne basins nominated for National Estuary Program, 1989

The Barataria and Terrebonne basins were nominated for participation in the U.S Environmental Protection Agency's National Estuary Program. In his nomination letter, the Governor of Louisiana stated, "Louisiana faces a pivotal battle in the Barataria-Terrebonne Estuarine Complex if we are to do our part in winning the national war to stem the net loss of wetlands."

Barataria-Terrebonne Estuarine Complexes accepted to National Estuary Program, 1990:

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the state of Louisiana committed to a cooperative agreement under the National Estuary Program to form the Barataria-Terrebone National Estuary Program. The Program was charged with developing a coalition of government, private, and commercial interests for the preservation of the Barataria and Terrebonne basins by identifying problems; assessing trends; designing pollution control; developing resources management strategies; recommending corrective actions; and seeking implementation commitments.

Act 637 of 1991 of the Louisiana Legislature, 1991:

Required the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources to develop rules and regulations for implementation of a Long Term Management Strategies Plan. The statute required beneficial use of any materials dredged from or deposited in coastal waters from the maintenance of any channel longer than one mile or where more than 500,000 cubic yards of material are moved.

The Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Restoration Plan, 1993:

The Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Conservation and Restoration Task Force, as mandated in the Breaux Act, or Coastal Wetland Planning Protection and Restoration Act (CWPPRA) completed the "Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Restoration Plan." The Plan provided a comprehensive approach to restore and prevent the loss of coastal wetlands. Using a basin planning approach, a number of needed projects were identified and the implementation of major strategies called for, such as the abandonment of the present Mississippi River Delta, multiple diversions in Barataria, reactivation of old distributary channels, rebuilding barrier island chains, seasonal increases down the Atchafalaya, reversal of negative hydrologic modifications, and controlling tidal flows in large navigation channels.

A Long-term Plan for Louisiana's Coastal Wetlands, 1993:

S. M. Gagliana and J. L. van Beek for the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources completed "A Long-term Plan for Louisiana's Coastal Wetlands." The Plan provided for comprehensive offensive and defensive strategies to be carried out in two 25-year phases. Key elements of the Plan included the establishment of a "Hold Fast Line", reallocation of Mississippi River flow with the establishment of phased subdeltas, estuarine management and an orderly retreat seaward of the "Hold Fast Line", and succession management of freshwater basins landward of the "Hold Fast Line." Volume two listed possible sources of funding for plan implementation.

Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, 1996:

The Management Conference of the Barataria-Terrebone National Estuary Program generated a list of potential actions that would help the Program achieve goals resulting is separate action plans.

An Environmental-Economic Blueprint for Restoring the Louisiana Coastal Zone: The State Plan, 1994:

The Governor's Office of Coastal Activities' Science Advisory Panel Workshop completed "An Environmental-Economic Blueprint for Restoring the Louisiana Coastal Zone: the State Plan" as directed by the Wetlands Conservation and Restoration Authority (State Wetlands Authority), under Act 6. The report provided a long-range blueprint for restoring Louisiana's coastal wetlands, which included several key provisions. The most important of these were: 1) diverting Mississippi River water and sediments into key locations; 2) restoring, protecting, and sustaining barrier islands; and 3) modifying major navigation channels to reduce saltwater intrusions and storm surge entry.

Atchafalaya Bay Delta Reevaluation project, 2000:

Initiated to address new alternatives for flood control and navigation. The alternatives included re-routing of the navigation channel, opening additional outlets from the upper basin, closing the lower Atchafalaya River outlet for lower river flows and delta management. The study was conducted with close cooperation from local, state, and federal resource agencies.

Terrebone voters pass a quarter-cent sales tax, 2001:

Terrebone voters passed a quarter-cent sales tax to help pay the local share of the planned $719 million hurricane-protection system. The local tax was estimated to raise roughly $4.5 million a year for the project. The state promised to match every dollar raised locally in order to pay for costs not covered by the federal government.

Legislative audit criticizes Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, 2004:

A legislative audit criticized the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources' division that oversees the coast for not doing a good enough job of ensuring that wetlands development is mitigated. The Department asked lawmakers to strengthen the department's enforcement and permitting rules.

Local government officials and business leaders push Congress, 2004:

Local government officials and business leaders pushed Congress for the Morganza-to-the Gulf hurricane-protection system, which aimed to protect Terrebonne from hurricanes and the Third Delta Conveyance Channel, which would channel fresh water from the Mississippi River to ailing local wetlands.

Geography

|

|

Land area in

square miles |

Persons

per square mile |

%

Population change 2000-2005

*

(2003) |

|

Point Coupe Parish |

557.34 |

40.9 |

-0.5 |

|

New Roads (city) |

4.60 |

|

-6.2 |

|

Baton Rouge(city) |

77.00 |

2,964.7 |

-1.5* |

|

Louisiana |

43,562.00 |

102.6 |

-4.1 |

Source: US Census Bureau 2000; 2004

(www.census.gov;

www.fedstats.gov)

1999 Economic Status

|

|

|

Point Coupe

Parish |

New Roads

(city) |

Baton Rouge

(city) |

|

Median Household Income |

$32,566 |

$32,256 |

$24,583 |

$ 30,368 |

|

Per Capita money Income |

$16,912 |

$15,387 |

$14,840 |

$18,512 |

|

Persons below Poverty Level |

19.6 % |

19.9 % |

23.6 % |

24.0% |

Source:

US Census Bureau 2000; 2004 (www.census.gov;

www.fedstats.gov)

Pointe Coupee Parish Facts

15,360 acres

of water

75,000

acres of pastures

150,000

acres of forests

Coldest Month:

January (Avg. 52° F)

Warmest Month:

July (Avg. 82° F)

Average annual temperature :

68° F

Average annual rainfall:

54.8 inches

Major Employers

|

Name |

Product/Service |

# Employees |

Union |

|

Louisiana Generating |

Private Utility |

330 |

Yes |

|

Nan Ya Plastics |

PVC Flexible Film |

250 |

No |

|

Newrich Industries |

Inflatable air mattresses, pool liners, plastic products |

130 |

No |

|

Bergeron Pecan Shelling |

Nut Packaging |

70 |

No |

|

JM Manufacturing |

PVC Pipe |

50 |

No |

|

Pointe Coupee Electrical |

Public Utility |

50 |

Yes |

|

Marionneaux Lumber Co. |

Lumber, wood chips |

40 |

No |

|

CRC Concrete Service (New Roads) |

Ready-mixed concrete |

12 |

No |

|

Alma Plantation, Ltd. |

Raw sugar, blackstrap molasses |

100(seasonal) |

No |

|

Georgia Pacific, Corp. |

Wood chips |

20 |

No |

|

Pointe Coupee Banner |

Newspaper publishing |

10 |

No |

Source: Ponte Coupe Chamber of Commerce (http://www.pcchamber.org)

Agriculture

Pointe Coupee Parish,

Louisiana

Select year intervals

Corn Production 1959-2006

Cotton Production 1954-2006

Year

Production (in bushels)

Year Production (in bales)

1954

14,000

1959

839,000

1955

10,400

1960

574,000

1960

4,060

1965

471,000

1965

6,000

1970

333,000

1970

2,240

1975

130,000

1975

260

1980

77,000

1980

0

1985

3,374,000

1985

0

1990

3,390,000

1990

12,800

1995

2,490,000

1995

22,600

2000

2,310,000

2000

19,000

2005

1,690,000

2005

17,400

2006

1,390,000

2006

22,600

Rice Production 1963-2006

Sorghum Production 1968-2006

Year

Production (in hundredweights)

Year

Production

(in bushels)

1963

17,800

1968

11,000

1970

40,000

1970

216,000

1975

38,400

1975

12,000

1981

62,000

1982

150,000

1985

53,000

1985

390,000

1990

64,000

1990

135,000

1995

150,000

1993

55,000

2001

150,000

2001

410,000

2005

125,000

2005

345,000

2006

120,000

2006

660,000

Soybean Production 1957-2006

Sugarcane Production 1975-2006

Year

Production (in bushels)

Year

Production (in tons)

1957

11,000

--

--

1965

57,000

--

--

1970

739,000

--

--

1975

910,000

1975

171,500

1980

3,150,000

1980

112,000

1985

1,700,000

1985

71,000

1990

3,330,000

1990

83,000

1995

1,950,000

1995

500,000

2000

2,430,000

2000

870,000

2005

2,570,000

2005

640,000

2006

2,420,000

2006

755,000

Agriculture

Pointe Coupee Parish,

Louisiana

Select year intervals

Wheat Production 1964-2006

1964

6,300

1965

4,400

1970

11,200

1975

3,000

1980

40,300

1985

490,000

1990

1,830,000

1995

505,000

2000

1,330,000

2005

1,120,000

2006

1,370,000

Source: LSA

Agricultural Center (http://www.lsuagcenter.com)