Cape Hatteras Background Information

North Carolina

Cape Hatteras & Cape Lookout Outer Banks

Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

Moving The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

Background Information

Cape Hatteras,

North Carolina

Summary information on the Cape Hatteras and the Outer Banks of North Carolina is a compilation of reports, articles, books, Open File government documents, Internet accessible data, and interviews with experts on barrier islands, wetlands, and change. Only direct quotes or facts are cited. General information from multiple sources and data from Internet websites are not cited. References consulted are located at the end of this summary.

Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout Outer Banks, North Carolina

To expect the shoreline on any coast to remain the same is unreasonable. The earth is a dynamic, living, changing object on which life depends. The erosion on the eastern sea board, the barrier islands protecting the shoreline of North Carolina in particular, is not an unusual or unexpected phenomenon. The eastern shore of Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Cape Lookout National Seashore are naturally eroding as the sea-level rises and redistributes sediment. Despite human engineering and creativity in an effort to divert the natural shoreline degradation, erosion continues, now threatening the structural stability of two historical markers on these barrier islands. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse now stands a mere 120 yards away from the retreating shoreline. Cape Lookout, too, is in danger of losing its foundation to the approaching sea.

The dynamic nature of the earth provides an expectation of surface change. Landforms in all geographic regions are subjected to redesign by wind, water, chemicals, and movement. Erosion and transport of sediments for the Barrier Islands of North Carolina are inevitable. But, the preservation of the lighthouses on the east facing seashores is an issue that brings all of the ecological and geomorphologic issues to the forefront of a barrier island and its morphology.

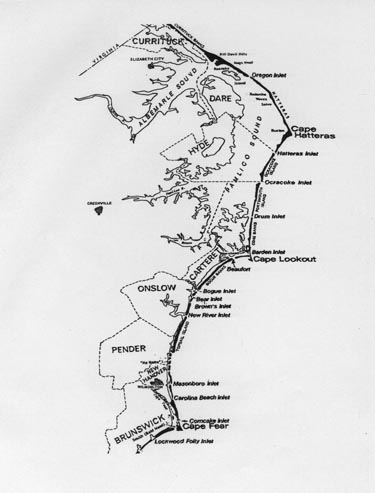

The focus for this study is to analyze the potential impact that these land changes have on the barrier island wetlands. The study recognizes the public issue of the historical Cape Hatteras lighthouse, the necessity of the still working Cape Lookout lighthouse, and the geographic changes that are a source of concern. This study explores the National Park Service (NPS) policies concerning the conservation and preservation of natural and historic objects, the changes--both physically and ecologically--that the Outer Banks of North Carolina have experienced, and the projected impact of further changes--both natural and human-induced-- will have on the Barrier Island system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of Cape Hatteras and Cape

Lookout on the

Outer Banks of North Carolina.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

The Outer Banks of North Carolina consist of a long, narrow strand of barrier islands broken periodically by various inlets to the Ablemarle- Pamlico Sounds and the mainland. Hatteras Island is near the middle seashores of the Outer Banks with an average width of 600 yards. The narrowest portion is only 200 yards, located about one mile north of Buxton. Cape Hatteras, positioned 280 miles further east than Palm Beach (the easternmost place on the Florida coastline), is the elbow of the Outer Banks, and has the highest probability of hurricane landfall in the Northeast. Located on the east facing shore, the Cape Hatteras lighthouse stands 225 feet tall, the tallest lighthouse in America. With a signal visible for 20 miles, the lighthouse was built in 1869, 1,500 feet from the shoreline, to warn Atlantic travelers of the area known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic." This shoal barrier has claimed more than 600 ships within its waters.

Seashore erosion has placed the historical building 120 yards from the shoreline, a position that leaves the lighthouse completely vulnerable to the energy of the sea. For several decades, there has been the fear that with one strong storm the lighthouse could topple and join the lost ships along the Atlantic coastline. The lighthouse was decommissioned in 1970.

Current plans are to move the lighthouse one-half mile inland to save the structure and maintain its historical significance. On October 16, 1998, President Clinton approved a request for $9.8 million to move the Cape Hatteras lighthouse.

Cape Lookout National Seashore and Cape Lookout Lighthouse

Cape Lookout, located south of Cape Hatteras and slightly north of the Barden Inlet, is also part of the North Carolina Barrier Islands. The area upon which Cape Lookout is positioned forms a sheltered embayment known as Lookout Bright. To the south and to the east of this inlet is a ten-mile long platform of shoals. It is here, overlooking the Lookout Shoals or "Horrible Headlands," that the Cape Lookout lighthouse was built. Constructed in 1859, the 160 feet tall structure with a signal visible for 19 miles, the remains in operation today.

Although the Cape Lookout lighthouse is not immediately threatened by the intrusion of the sea, the effects of erosion and displacement are at work on the National Seashore. The unknown fate of the Cape Hatteras lighthouse cast a shadow on the existence of the Cape Lookout lighthouse.

The interactions that occur between an island and the sea are obvious to any beach vacationer; the characteristics of one are affected by the other. The natural development of a barrier island is a constant process of building, tearing down and rebuilding. In terms of geologic time, a barrier island is a temporary physical feature. The complexity of the land-sea interaction usually reveals itself during major tropical storms and hurricanes when the thrust of wave action, torrential rains, and strong winds change the shore and island landscape. Change is a natural process. For a barrier island, natural instruments of change include sea-level rise, wind patterns and seasonal storms. One recognizable commonality is the constant movement that pushes the island toward the mainland.

Rising waters continuously reshape land formations of the Core Banks. The natural movement of a barrier island is to migrate landward as sea-level rises. The elements of land (sand, soil, and sediments) move in some thing similar to a leap-frog motion. For the island to be moving toward the mainland two things must happen: 1) the ocean must erode away the front side of land and 2) the back side (sound side) must grow, continuing to crawl toward mainland (Pilkey 1980, 20-27).

Sea-level rise is a major contributor to ocean-side erosion. Hydraulic characteristics of elemental break down and effective stress provide tools for erosion. The tides carry away and redistribute the beach horizontally. This coastal erosion is referred to as shoreline retreat.

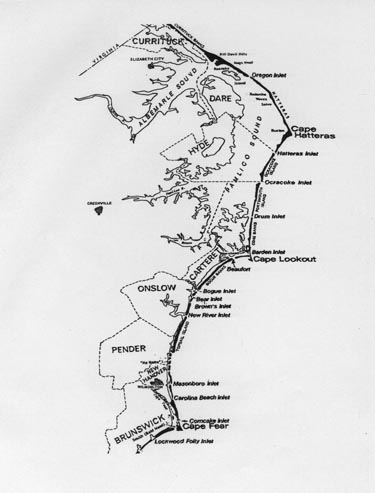

Sound side growth has two major elements. The first is a process involving the formation of inlets mostly during major storms. The motion of the ocean tide carries sand through an inlet, providing land building material for a tidal delta formed by relocated sand. Eventually the build up of sand will turn a shallow delta into a salt-marsh on which vegetation can grow, contributing greatly to the continued construction of sound side land. This tidal delta eventually can close off the sound inlet, but the natural system of seasonal storms may open a new one if it is not simply laterally.

Frontal overwash, a result of storm wave action, is the second major contributor to land building. The water brings displaced sand from the front to the mid or back sections of the island, adding to the building of land towards the main land (Figure 2). This method of construction is most prevalent on a narrow island such as Cape Hatteras Island.

The effects of the salt-laden wind is evident in the vegetation and climate of the island. Dwarf woodlands reshaped for protection are physical evidence of the molding power the ocean winds have on the barrier islands. The wind also plays an active role in land displacement and relocation. The natural building of dunes within the island provides a windward protection for the sound side of the island, but this still does not completely halt the influence of the wind.

Figure 2: Inlet Formation

Powerful storms hold the most visible and dramatic land reformation effects simply because they redistribute large quantities of soil in a relatively short period of time. Tropical storms and Hurricanes making land fall anywhere along the barrier islands are usually considered "destructive," but in actuality are a crucial part of the ongoing process of tearing down and rebuilding.

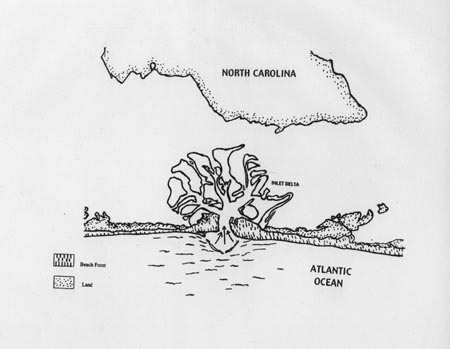

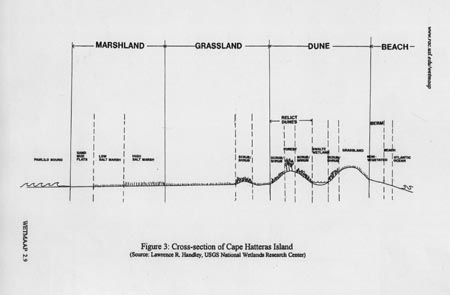

Barrier island environments change as one moves from the back (sound side) to the front (ocean side). Moving from the sound to the ocean, the Core Banks can be divided into five sections of interrelated environments: marshlands, grasslands, dunes & overwash, the berm and finally the ocean front beach. Within these five major divisions there are subdivisions which play specific roles in the island’s existence (Figure 3).

The marshlands can be sectioned off by the build up of lagoon sediments and are divided into two sections: sand flats and salt marsh. Below Mean Sea Level (MSL), sound side, vegetation takes root stabilizing the new addition of sediments and adding to the growth of the sound facing side. Sand Flats begin to surface in the low tide flats, although they still can be under MSL. The sand continues to build in this area trapped by marsh vegetation.

Salt marshes are divided into low marsh and high marsh area. The low marsh is composed of emergent salt tolerant vegetation subjected to daily tidal inundation. High marsh areas of salt tolerant emergent vegetation is subjected to intermittent inundation from high wind-driven tides.

The island increases in surface area and elevation inland. Higher, broader, and somewhat protected, this mid section consists of overwash layers and nutrient soil. The barrier flats support the herbaceous grasslands and woody scrub-shrub vegetation. Forests of salt-wind pruned woodlands of oak, cedar, and yaupon holly occupy the higher and more stable landscapes of the Outer Banks.

Figure 3: Cross-section of Cape Hatteras Island

The highest elevation on barrier islands are dunes, which are the result of wind blowing sand particles. Dunes "hide" the inland growth from the ocean tides.

During powerful storms or high wave activity, however, the dunes cannot protect the grasslands and salt marsh from the sea. The overwash leaves behind a layer of spread sand called an overwash fan. The wind and, to a more limited extent, water transport the loose overwash and beach sand to help rebuilt the dunes.

Berms, highlands of the beach that slope away from the crest of the dunes, form the back shore. This area is relatively flat, covered with sand and little vegetation, and us washed by intermittently high wind-driven tides.

A distinct drop of land signifies the berm crest, which falls into the foreshore. This area is highly transitional and falls below MSL. The beach is non-vegetated and subjected to daily tidal actions.

Environmental changes of a natural system are quite different than those of a human altered system. The Core banks off the Carolina mainland have not been left unaltered by human intervention.

Although erosion is a natural process, humans have adapted the land to suit their needs and, in turn, increased the erosional process due to excessive use and modification. Erosion on the sound side of the barrier islands also reflects human impact including recreational use and residential development that inhibits natural changes. The increase of wave action induced by boat wakes, the removal of sand from the sand flats, and the thinning of the woodlands affect the reversal of natural growth and change.

Despite efforts to save the ocean front beaches, human intervention has actually increased the erosion process. By placing steal groins in the nearshores of some of the islands (i.e., Hatteras), preservation efforts have effectively starved beaches down-current. The ecosystems of the barrier islands are interdependent within themselves and they are interactive with each other. The "trough" movement of water transports sand and sediments from the northern to the southern portion of the barrier island. By confining the sand in one area, erosion nearly doubles further down the shoreline.

The thin strip of islands of North Carolina’s Outer Banks share a common culture and historical heritage. The Wright Brother’s National Memorial on Bodie Island is a heritage site important to cultures worldwide.

Five grand lighthouses, strategically placed on the Outer Banks historically served to warn seafarers about the staggered shoals and dangerous waters along the coastline. Because of the numerous shipwrecks, the area became known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic." These treacherous waters, including Lookout Shoals or the "Horrible Headlands" just beyond the banks of Cape Lookout and Diamond Shoals stretching out from the easternmost point of Cape Hatteras, have claimed over 600 ships.

The National Seashore lighthouses offer a cultural heritage dating from the 16th Century. Historically, local residents served as light-keepers, as members of the U.S. Life Saving Service or, in later years, with the U.S. Coast Guard. Current Barrier Island residents, local and state legislatures, and preservationists recognize the historic value of the lighthouses as warning devices and as lifesaving stations. Designation of major portions of North Carolina’s Outer Banks as part of the National Park System indicates its value as a natural scenic and historic seashore.

Preserving and preventing erosion of the Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout lighthouses has been a focal issue for many years. After multiple investigations and meetings for solutions to the threat of erosion undermining the foundation of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, it has been decided that the best method for preserving lighthouse is to move the it to a new location. Yet, controversy surrounds this decision

The major natural change causing structural concern for both Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout Lighthouses is the threat of erosion. In both cases, the east-facing shore is subjected to the onslaught of high winds, sea-level rise, and fierce storms, all of which cause the removal and relocation of seashore sediments. While erosion continually narrows the east-facing shore of the barrier islands, the southern shore below Cape Point accumulates sand, extending the island south ward. (Paulson 1988).

Between 1945 and 1992 the shoreline retreated about 130 feet, an average rate of 5.6 feet per year. Recently, that rate has increased to nearly 10 feet per year. Three steel groins were built around Cape Hatteras in 1963 in an effort to divert the effects of erosion. This effort had a minimal impact on the retreating land. Unfortunately, the placement of these groins actually has accelerated the effects of erosion. In 1997, the distance between the shoreline and the Cape Hatteras lighthouse was reported to be only 120 yards, just over the length of a football field.

As the threat of erosion continues each year, the imposing sea encroaches upon the land and the historical lighthouses. The obvious threat posed by erosion also indicates a threat to the ecological systems of the Outer Banks. The natural resources also change due to the continuing erosion of the eastern shoreline.

Moving the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

The current plan to move the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is not the first attempt to save the lighthouse. There was a "penny drive" by children in the 1980s to raise money to preserve the lighthouse.

The controversy of moving the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse brings to the forefront the underlying issues of continuing sea-level rise, the onslaught of constant storms, and the domino effect of removal and over use of natural resources. The Army Corps of Engineers has examined the threat of erosion to the Outer Banks since the 1930s. The Corps continually proposes methods for preventing shoreline erosion including the building of a coffer dam around the Lighthouse in the 1960s — a costly stopgap without a guarantee for success because of strong Atlantic wave action and seasonal storms. While the threat of erosion is prevalent throughout the Outer Banks, the possible loss of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse forces attention to the ecological issues at hand.

The natural migration of the barrier island toward mainland has led to a recommendation by some that the Lighthouse be left to the sea, or left to the natural course of shoreline retreat. To others, this signifies the loss of a heritage; a land mark that has served a very useful, lifesaving purpose. Perhaps, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse represent a losing battle with the elements of nature--or perhaps it is a warning that human intervention exacerbates barrier island change and land loss. In any case, the lighthouse has cast its beam on the important environmental issues affecting the barrier islands, wetland development, and the foggy future of natural and cultural resources.

Godfrey, Paul J. and Melinda M. Godfrey. 1976. Barrier Island Ecology of Cape Lookout National Seashore and Vicinity, North Carolina. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington D.C.

Erosion Study Cape Look Lighthouse Study. 1978. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Wilmington, N.C.

Bennett, Gordon D. 1996. Snapshots of the Carolinas: Landscapes and Cultures. Association of American Geographers; Charlotte, N.C.

Benhart, John E. and Alex Margin. 1994. Wetlands: Science, Politics, and Geographical Relationships. National Council for Geographic Education; Indiana P.A.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, North Carolina Fourth Groin Alternative Design Report and Environmental Assessment. 1996. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Wilmington District.

Cape Lookout National Seashore, Discussion of Alternatives. 1998. National Parks Service Southeast support Office Planning Division. Atlanta, G.A.

Pilkey, Orrin H. Jr., William J. Neal, Orrin H. Pilkey, Sr., Stanley R. Riggs. 1978, 1980. From Currituck to Calabash: Living with North Carolina’s Barrier Islands. North Carolina Science and Technology Research Center; Research Triangle Park, N.C.

Paulson, Lee (Editor). 1988. Saving Cape Hatteras Lighthouse from the Sea. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.

Stick, David. 1952. Graveyard of the Atlantic: Shipwrecks of the North Carolina Coast. The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.